One of the unspoken truths of the study of religion is that it has an unacknowledged, problematic sibling in paranormal studies. There are many obvious differences: for one thing, religious study is respectable, if not really considered essential, whereas paranormal study is suspect and not generally acknowledged by established scientific or mainstream research institutes. Nevertheless, both religion and paranormal phenomena deal with unquantifiable experiences, aspects of human perception that cannot yet be measured. So it was with a large grain of salt that my wife signed me up for a year’s subscription to the TAPS Paramagazine. I’ve posted on this particular magazine before, but a new issue arrived just yesterday that contained so many references to the Bible and mainstream religion that I thought it worthy of reiteration.

In general I am skeptical about supernatural claims. At the same time, I am aware that we understand only a fraction of the universe and some aspects of theoretical physics are more bizarre than your average ghost story. When the magazine arrives I read through it with my salt-shaker within easy reach. Nevertheless, a feeling haunts me that at some deep level my specialization is connected with paranormal activity. The first article in the current issue concerns the Underworld. The author suggests that biblical and Mesopotamian references to the Underworld may be supported by the findings of ghost hunting investigators.

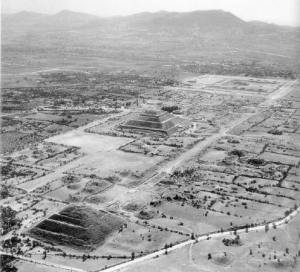

I’m all for a couple of working guys (plumbers Jason and Grant) daring to tread where scientists fear to go, but the problems of using ancient materials to bolster ghost-hunting claims are legion. Just a glance at the popularity of Zecharia Sitchin books warns against a simplistic reading of complex, ancient civilizations. We don’t need ghosts in the machine to explain the Sumerians or Babylonians. At the same time, we don’t have many academic options for uncovering the many, many ghost claims that have made throughout history. Mass neurosis is less believable than occasional hauntings. So although I have to disagree about the viability of a literal Underworld – a good understanding of ancient mythology helps to clarify that one – I do reserve some space for wondering if religious studies might not end up in the same final resting place as paranormal studies once science is able to penetrate the veil.