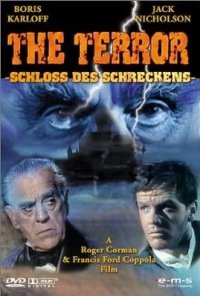

Saturday afternoons were made for B movies. After a hectic week, nothing soothes like grainy picture quality and poor dialogue. This weekend offered a chance to view The Terror. This 1963 Roger Corman film won its bad marks the honest way – by earning them. Nevertheless with Jack Nicholson playing against Boris Karloff and a plot so convoluted that I had to draw a chart to figure out what I’d just watched, the movie lived up to its grade. Throw in Francis Ford Coppola as an associate producer and it’s party time. Corman’s legendary cheapness and fondness for disproportionate claims of scares that never materialize only add to the charm. After watching the opening sequence one gets the distinct impression that Franklin J. Schaffner had watched this film before setting up the climatic scene of Planet of the Apes.

In keeping with a recent trend on this blog, the plot involved a witch. An old woman from Poland resettles in France to avenge her murdered son. The crone casts a spell transforming a bird into a beautiful young woman. The first words of the spells sent me fumbling for the “rewind” button. “Tetragrammaton, tetragrammaton,” the old woman intones to begin her spell. In a movie fraught with dialogue problems, this might be considered simply a choice of foreign-sounding, mysterious syllables to be uttered for an audience not expected to know that tetragrammaton is the title of the sacred four-letter name of Yahweh. By this point the plot was so convoluted that making God the agent behind a pagan curse seemed almost natural.

The analog with the Bible soon became clear. The Bible holds its sway over many because of its often beautiful rhetoric. Sparing the time to study what the rhetoric might have meant in its original context is an exercise few believers can afford to undertake. Our world has become so full of things that taking time to explore the implications of one’s religion must compete with ever increasing Internet options, thousands of channels of television, and plain, old-fashioned figuring out how to get along. Religion is a luxury item and, as experience tells us, it is best not to look too closely at luxuries – their flaws too readily appear upon detailed inspection. Allowing religion its exotic sounding mumbo-jumbo preserves its mystery and power. And if a witch says a theologically freighted word we can just chalk it up to entertainment. We are too busy to examine what our religions really say. Roger Corman may have unintentionally discovered a real terror in a movie that will keep no one awake at night.