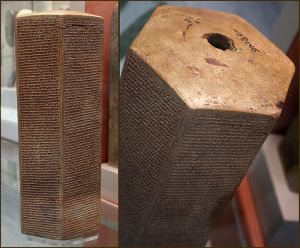

Civilization began in the “Middle East.” Ever since then, it has been a struggle to keep it together. One of the sad realities of the last century and continuing into this is that peace in this region seems as elusive as a Tea Partier with compassion. Claims to land are among the most complex of human inventions. Having never been a property owner, I’ve only ever watched this from the sidelines, but I know the endless surveying, assessing, and negotiating that goes into drawing invisible lines across the surface of our planet in order to determine who owns what. At least as early as the Code of Hammurabi, the placing of property markers was considered the concern of the gods. Humans are clearly among the most territorial of animals.

When my wife showed me a CNN story about an archaeological dig at Khirbet Qeiyafa in Israel, this old issue raised its weary head once more. The site, whose ancient name is not yet known, is being suggested as “the city of David” by archaeologist Yosef Garfinkel. The evidence for the suggestion, as far as I can tell from news reports, is that the city fits the right time period and lacks pig bones. With the Bible’s great claims for David’s very large kingdom, archaeologists have been unable to find evidence that such a grand entity ever existed. David himself is not historically attested outside the Bible. Those who make land claims based on a putative gift of God, however, must find physical evidence to back it up. This wish hovers like a dove over every excavation.

Archaeology has frequently been commandeered by special interest groups. The field of study began in the “Middle East” to find evidence for the historicity of biblical stories, some of which were never intended as history. Daunting emotional claims, however, weighed heavily on the minds of those who led the excavations. The Bible made what they supposed to be historical claims, so the physical evidence had to back it up. When Jericho was excavated and found to have been abandoned at the time of Joshua not a few heads were scratched. Archaeologists returned to the city in later excavations to try to question the results. Jericho was a ghost town long before Joshua came along because the story of Jericho has something more important than history to convey. That larger message, applicable throughout the world, seems to be: don’t base claims to special privilege on the Bible. Tea Partiers could even learn a thing or two from that message as well.