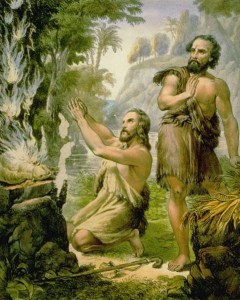

As I tweet the Bible into cyberspace, Cain strikes me as a most misunderstood character. Mercilessly portrayed as an ungrateful boor, the first vegetable farmer in folklore is demonized as the father of all sinners. Genesis, however, is impossibly vague on Cain’s crime. A close reading of Genesis 4 indicates that Cain was the first human being to offer a sacrifice to a higher power. Being a tiller of the soil, that sacrifice was of the fibrous kind, bereft of any fat or blood. The divine nose (metaphorically) is turned up at this attempt at pacification. In steps Abel with his bloody slaughter of animals and God is well pleased. Traditionally, Christian readers have attributed Cain’s evil intent toward Abel as jealousy. Genesis doesn’t seem to bear this out. “But unto Cain and to his offering he [the Lord] had not respect.” Cain was not jealous, but “wroth.”

Much later in time Paul of Tarsus will tell fledgling Christians that God is “no respecter of persons.” Still, in that first moment of divine favoritism, prior to any explicit instruction being given, we catch a glimpse of the future of this nascent religious movement. Even today, the literalists tell us, God expects something from us. What, exactly, differs from interpreter to interpreter. Cain’s crime was simply being human. Even more poignant in this case is the fact that the divine allowance for consuming meat has not yet been made. Abel raises animals for God’s appetite while Cain raises vegetables for human consumption. No sentient being is harmed in Cain’s offering. Abel, one might say, is the first killer in human history.

We all know the story. Cain will rise up against his brother and slay him. He will then receive a prototype of the mark of the beast and scamper off to rustle up a wife somehow. All this before the third natural born human being, Seth, is even conceived. Beowulf will reflect Cain’s dilemma centuries later, as Grendel is the spawn of the first murderer. The descendents of Cain are routinely demonized while the children of Seth repeat the cycle of divine favoritism over again. Here is Cain’s problem: God will like whom God will like. The rest cannot earn divine favor. The bloody consequences of this reading of history continue to play themselves out even today. Those who need divine approbation will go to any lengths to feel special, while all of us, the true heirs of Cain, have to work it out as best we can under silent skies.