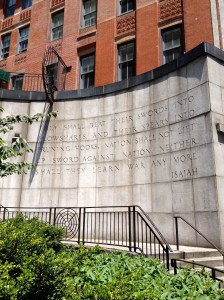

In my youngest days the word “occult” conjured the most perilous kind of fear in my inexperienced, Christian heart. It sounded malevolent and sinister, suggesting Hell, Satan, and the coercion of the divine. Therefore it took considerable time to pump up the courage to read Occult America by Mitch Horowitz. Well, maybe it wasn’t that dramatic—I learned in the course of my many years studying religion that “occult” is very difficult to tease out from “religion.” What I really feared is what others would think of me as I sat on the bus reading Occult America while heading to the Lincoln Tunnel. The word “occult” refers to the “hidden” or “secret” nature of certain religious practices. In ancient times it might refer to the Gnostics or Mandaeans, while in more recent days it might be used to describe Rosicrucians or Theosophists. Unconventional, yes. Evil, hardly.

In my youngest days the word “occult” conjured the most perilous kind of fear in my inexperienced, Christian heart. It sounded malevolent and sinister, suggesting Hell, Satan, and the coercion of the divine. Therefore it took considerable time to pump up the courage to read Occult America by Mitch Horowitz. Well, maybe it wasn’t that dramatic—I learned in the course of my many years studying religion that “occult” is very difficult to tease out from “religion.” What I really feared is what others would think of me as I sat on the bus reading Occult America while heading to the Lincoln Tunnel. The word “occult” refers to the “hidden” or “secret” nature of certain religious practices. In ancient times it might refer to the Gnostics or Mandaeans, while in more recent days it might be used to describe Rosicrucians or Theosophists. Unconventional, yes. Evil, hardly.

Horowitz takes his readers through a whirlwind tour of some very colorful characters and, perhaps more importantly, shows just how deeply rooted occult practices are in the most Christian nation on earth. Few people realize just how influenced high office holders in this country have occasionally been by the occult. It seems a hard-and-fast rule that to be elected president you must be a professing Christian, strongly preferable if of the evangelical, Protestant flavor. Ronald Reagan made a great show of that while being personally convicted of the efficacy of astrology and some popular mediums. And Reagan has not been the only one. Still, politicians have to keep their more unconventional religious beliefs secret. The populace likes a straight shooter, devotionally speaking. The fact is that even what many people think of as regular Christianity has been seasoned somewhat with occult.

I can recommend this little book for getting a sense of just how deeply the occult has tunneled into the American psyche. The chapter on the ouija board took me straight back to a very straight-laced Grove City College, bastion of conservative evangelicalism. When I matriculated (which sounds vaguely occultish in its own right) the yearbook was called The Ouija. It was explained away as the combination of the French and German words for “yes,” but everyone knew, given what yearbooks are, that it had that spooky, occult vibe. By my senior year a more fluffy, evangelical-safe title of The Bridge replaced it. And many heaved a great sigh of relief. Christians thanked their lucky stars that they’d been delivered from the evils of the occult just as they were lining up to elect Ronald Reagan to a second term in office.