Scientology has been back in the news with the divorce of Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes. Media pundits like to point out the highly unorthodox nature of Scientology, but such critiques overlook the vital nature of New Religious Movements. Many of us are raised believing that religions, to be “true,” must possess at least a modicum of antiquity. We routinely reject the science of the first century of the common era (well, maybe the Creationists don’t), but we accept without question that the religious views of the time were on-spot and unchanging. It comes as a surprise, therefore, when a new religion like Mormonism or Scientology prospers. Accusations of being money-driven are rife, but then, who has recently audited the Vatican or CBN? Religions are “non-profit” by definition, but they certainly do raise money. As players in the capitalist game, I say more power to them. Who else can make tremendous profits and claim tax-free status (apart from major corporations, I mean)? Most believers are happy to throw a few dollars in the direction of some guru who will deliver him or her from hell, at least.

The fact that true believers in revelation don’t like to face is that every religion started some place. It would be a different story were there only one religion that ever developed, but as soon as someone started to declare their belief orthodox it was only a matter of time before heterodoxy joined the conversation. In the light of this wide-open world of religious beliefs, I think that creativity has been undervalued all along. Say what they might, critics have to admit that Mormonism, Scientology, and even Jehovah’s Witnesses have to score high on the originality scale. Since Yahweh has a lot of competition in the deity market these days it will be difficult to find an adequate final arbiter.

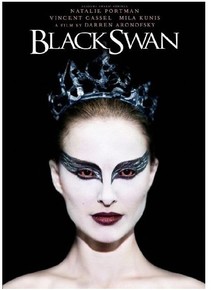

I would like to suggest a panel of experts, like on the appropriately titled “American Idol.” Gods are often hard to pin down, even with email and Twitter and Facebook. To fill in our distinguished panel of judges, then, who might we choose? The clergy of any tradition, I’m afraid, will be biased and so we might look elsewhere. Politicians too should be excluded since their remit is exploitation. Besides, they don’t often recognize creativity as something worth funding. Where does that leave us? We can’t use the average person, because who is going to watch their peers on television. Famous people. An athlete would be a good choice since overthinking religions can lead to trouble. We might need to avoid Tebow, however. Hollywood is said to be godless, so an actor would have great appeal—besides, good looks must equate to good theology, mustn’t they? Who will our third panelist be? Probably a writer; they are creative and their names are well-known. They would add intellectual heft without having the same star status as their more visible colleagues. Funny, L. Ron Hubbard was a science fiction writer whose religion thrives in Hollywood and who enjoyed the sport of yachting. We may have our winner here!