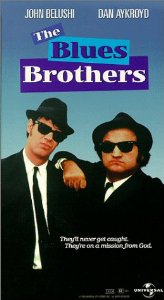

Coming back to The Blues Brothers after a couple of decades proved to be a kind of personal enlightenment. Of course I remembered “We’re on a mission from God,” as a catch-phrase, but in the intervening years I’d forgotten what that mission was. The movie is, as it were, backstory for the Saturday Night Live sketch in that show’s halcyon days. Watching the movie as an adult I was astonished at how positively religion is portrayed. Jake and Elwood’s mission is to save their childhood Catholic orphanage. Although there are a few laughs at the expense of religion, the movie as a whole is a redemption story with a surprising lack of irony. Released from prison where he was doing time for trying to do the right thing, Jake has an authentic religious experience and from that point on, the mission is unquestioned. In a self-sacrificial move that lands the whole band in prison, the Blues Brothers pay the taxes owed and save the orphanage. They are doing time for saving poor children.

I reflected on how, since 1980, it has become difficult to find mainstream movies that are so positive toward religious values. Not coincidentally, the 1980s saw the tragic Reagan years when religion and politics blended to the permanent detriment of religion being taken seriously. Since that time the cynicism has grown considerably. We are constantly reminded of it as conservative pundits force “Christianity” into a more and more reactionary mode, condemning all that reason has finally released from the dark ages. This is religion which thrives in the darkness of ignorance and fear. And it has coopted the very definition of religion itself. It is hard to imagine a “mission from God” being taken half as seriously today as it was when Jake and Elwood, although personally irreverent, nevertheless take the ethical call so seriously.

Today the “mission from God” is to protect one’s personal investments. Shut out those who require special consideration or those whose lifestyle differs from that which is putatively biblical. Anyone who dares step out of line is, in this enlightened era, condemned to the outer darkness. The Blues Brothers always wore dark glasses. While initially a branding gimmick, even this has symbolic value in the public view of religion. After all, Roman Catholic Sister Mary Stigmata gives them a sound thrashing for their profane language. But they find the truth in a black, evangelical service. There is a tolerance here—the neo-Nazis end up buried in their own grave—that has since vanished. The dark glasses hide something vital. The only time they are removed in the movie is to deceive. I wonder, I just wonder if with the glasses removed Jake saw a future for which the only prudent response was to hide once again.