I had almost forgotten the validation of being published. Colleagues sometimes ask me if I’m still working on any books without realizing that employment in publishing, with rare instances, constitutes a conflict of interest. Editors are acquirers of content, not producers thereof. As I’ve been preparing Weathering the Psalms for release on the world, I often consider how differently all this may have turned out, should I have found academic employment after Nashotah House. The day my contract was terminated, I was working on this book. It had recently been declined by Oxford University Press, and the reviewer (whom I had unwittingly met) had informed me that the book wasn’t really salvageable. It was a jumble of data with no narrative thrust. I was working on giving the data a different frame when I was called to the Dean’s office and told to read a legal memo in the presence of a lawyer. Every time I tried to turn back to my book after that, the nightmarish scene replayed in my head. Besides, I had to try to find a job.

I had almost forgotten the validation of being published. Colleagues sometimes ask me if I’m still working on any books without realizing that employment in publishing, with rare instances, constitutes a conflict of interest. Editors are acquirers of content, not producers thereof. As I’ve been preparing Weathering the Psalms for release on the world, I often consider how differently all this may have turned out, should I have found academic employment after Nashotah House. The day my contract was terminated, I was working on this book. It had recently been declined by Oxford University Press, and the reviewer (whom I had unwittingly met) had informed me that the book wasn’t really salvageable. It was a jumble of data with no narrative thrust. I was working on giving the data a different frame when I was called to the Dean’s office and told to read a legal memo in the presence of a lawyer. Every time I tried to turn back to my book after that, the nightmarish scene replayed in my head. Besides, I had to try to find a job.

It was only when working for what I thought was a stable Routledge that I had the chance to revisit the manuscript. Ironically, it was only after I was no longer in a position to do research that colleagues began to approach me to review submissions for journals, to invite me to write articles, and to express an interest in my research. Of course, it was too late for me to begin full-fledged research again. Despite the internet, scholars require two things I did not (do not) have: access to a university library, and time. Early on in my commuting days I discovered that the quality of the time on the bus did not allow for in-depth research. Too many other passengers have too many other agendas. I can read on the bus, and sometimes academic books, but anyone who’s tried to take notes when crammed into the space usually taken up by a backpack knows the difficulty of writing notes without the use of your arms or hands, over the constant electronic noise of your neighbor’s unsilenced electronic games.

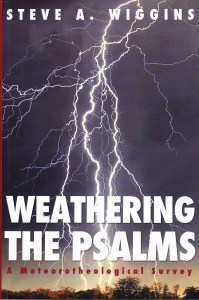

All of which is to say that I’m very pleased to see Weathering the Psalms is out. Like a child untimely born—at the risk of sounding biblical—the book is being printed as I write. Working in publishing I know better than to expect phenomenal sales, still, many of my readers over the years have said they’d buy a copy if it was ever published. If you’re serious about that, take a look at the website of Wipf & Stock and click on the Cascade Books imprint. Finishing this book has, I must admit, awakened a hunger. I have, of course, started to write another. It may be another decade in the making, and, should it ever garner the attention of a publisher, a similar post may come along before I’m too old to think clearly. The ideas are there; the opportunity to express them is not. Still, despite the cruel vagaries of academia, I feel as though I’ve received a small validation, and I am very grateful for the honor. Wipf & Stock offers a service that other academic presses might do well to emulate. It’s not all about the earning potential of a title. Sometimes it’s just a storm.