Noah’s Ark has a way of showing up in many literary forms. Familiar to many from Genesis, it actually predates the Good Book by hundreds of years. On the backside, it keeps recurring in literature as diverse as Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, Jonathan Carroll’s The Ghost in Love, and Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy. It also shows up in Bill Broun’s debut novel Night of the Animals. Set in a future that’s becoming present faster than Broun likely anticipated, the story revolves around an addict who hears animal voices. The story stubbornly refuses to let you get any grip on a slippery reality, so the reader’s left guessing even at the end. In the 2050s Britain is under a fascist regime that seeks to keep the wealthy happy and everyone else servile. (Keep reminding yourself this was written before 11/9.)

Noah’s Ark has a way of showing up in many literary forms. Familiar to many from Genesis, it actually predates the Good Book by hundreds of years. On the backside, it keeps recurring in literature as diverse as Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, Jonathan Carroll’s The Ghost in Love, and Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy. It also shows up in Bill Broun’s debut novel Night of the Animals. Set in a future that’s becoming present faster than Broun likely anticipated, the story revolves around an addict who hears animal voices. The story stubbornly refuses to let you get any grip on a slippery reality, so the reader’s left guessing even at the end. In the 2050s Britain is under a fascist regime that seeks to keep the wealthy happy and everyone else servile. (Keep reminding yourself this was written before 11/9.)

Cuthbert, the protagonist, believes the animals—most of which are extinct in the wild—are calling him to release them from the London zoo. As an addict his perception of reality is constantly in question. His sense of mission, however, is not. One of the stranger elements in the tale (and that’s saying something!) is the revival of Heaven’s Gate. This cult, instead of wiping itself out, has gone international. The approach of a comet sets the Neuters (as they’re called) on a mission to wipe out earth’s remaining animals. Many of them are in the London zoo, which brings Heaven’s Gate into direct conflict with Cuthbert, who is busy trying to release as many talking animals as possible. London literally becomes a zoo and Heaven’s Gate openly attempts a coup.

All of this sounds wild and fantasy-prone, but like 1984, fiction sometimes peers deeper into reality than science. Is it science fiction? It’s set in the future, but it’s difficult to say. What has all this to do with Noah’s Ark? The novel itself draws the parallel—the zoo that preserves the last of their kind is, by default, an ark. The Ark. Floating on a world-ocean of irrational turmoil where might (read wealth) makes right after all. Religious imagery interlards the story. Cuthbert becomes St. Cuthbert. His possible granddaughter (the reader is never sure) manifests as the Christ of the Otters. There’s even a kind of Second Coming. This is a novel that feels like altered reality. That illusion is given the lie when you close the book and turn on the news.

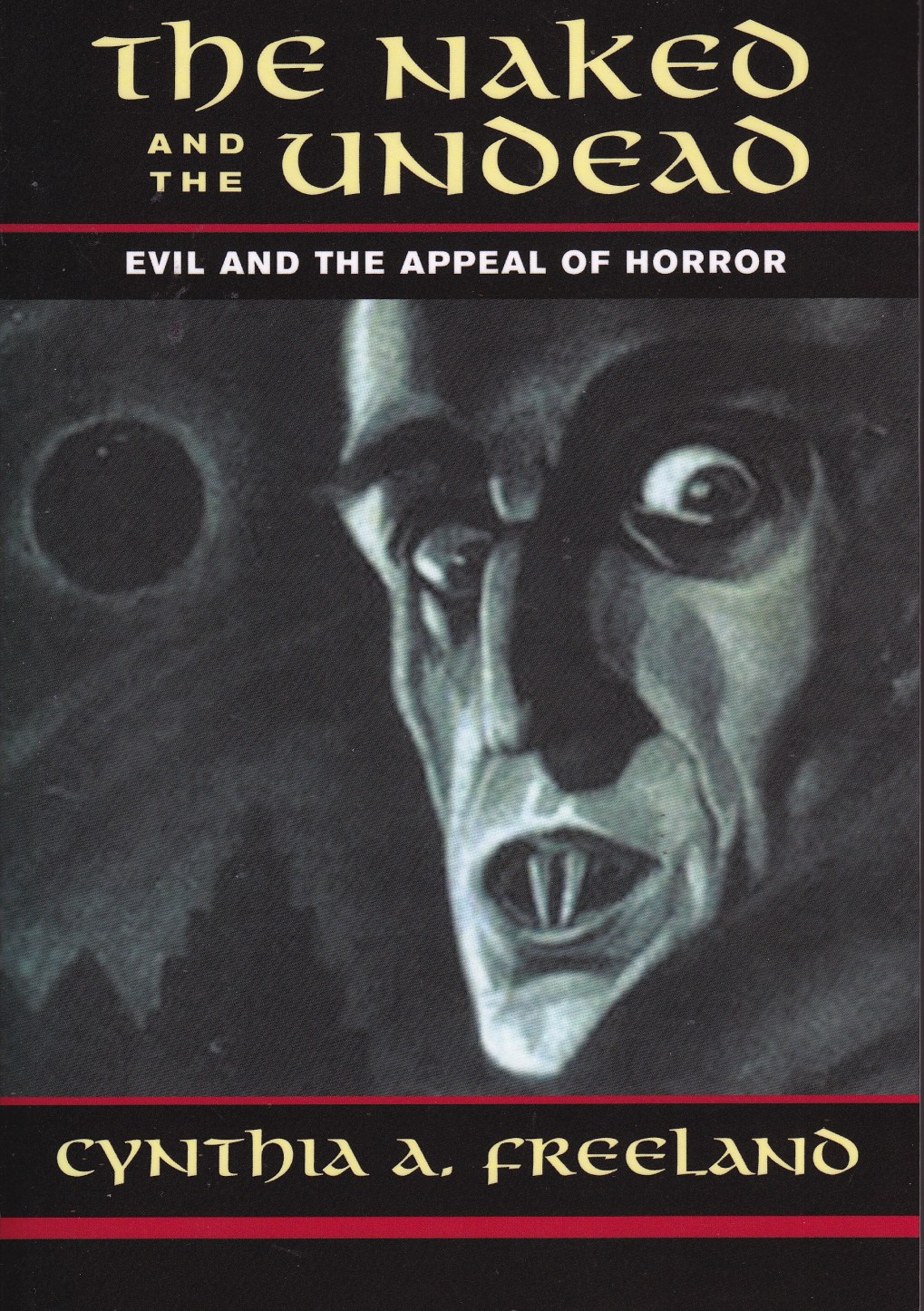

Good and evil. Well, mostly evil, actually. No, I’m not talking about Washington, DC, but about horror movies. Cynthia A. Freeland’s The Naked and the Undead: Evil and the Appeal of Horror is a study that brings a cognitivist approach to the dual themes of feminism and how horror presents evil. It’s not as simple as it sounds. Like many philosophers Freeland is aware that topics are seldom as straightforward as they appear. Feminists have approached horror films before, and other analysts have addressed the aspects of evil that the genre presents, but bringing them together into one place casts light on the subject from different angles. Freeland begins this process by dividing her material into three main sections: mad scientists and monstrous mothers (which allows for the Frankenstein angle), from vampires to slashers, and sublime spectacles of disaster. Already the reader can tell she’s a real fan.

Good and evil. Well, mostly evil, actually. No, I’m not talking about Washington, DC, but about horror movies. Cynthia A. Freeland’s The Naked and the Undead: Evil and the Appeal of Horror is a study that brings a cognitivist approach to the dual themes of feminism and how horror presents evil. It’s not as simple as it sounds. Like many philosophers Freeland is aware that topics are seldom as straightforward as they appear. Feminists have approached horror films before, and other analysts have addressed the aspects of evil that the genre presents, but bringing them together into one place casts light on the subject from different angles. Freeland begins this process by dividing her material into three main sections: mad scientists and monstrous mothers (which allows for the Frankenstein angle), from vampires to slashers, and sublime spectacles of disaster. Already the reader can tell she’s a real fan.