Lots of people write for lots of reasons. Some love it. Some hate it. Some can’t help themselves. For those who know me primarily through this blog, it may not be obvious which of these sorts I am. After having read Dani Shapiro’s Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life I finally feel confident putting myself in category three. It’s not that I don’t like writing—I live for it. The kind of person Shapiro describes, however, is the one who defines their entire being through writing. Each day I post between 300 and 500 words on this blog. I’ve been doing it since 2009, which means I’m somewhere over the million-word mark. But those compelled to write will never be satisfied with just that. One does not live by blog alone, after all.

Lots of people write for lots of reasons. Some love it. Some hate it. Some can’t help themselves. For those who know me primarily through this blog, it may not be obvious which of these sorts I am. After having read Dani Shapiro’s Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life I finally feel confident putting myself in category three. It’s not that I don’t like writing—I live for it. The kind of person Shapiro describes, however, is the one who defines their entire being through writing. Each day I post between 300 and 500 words on this blog. I’ve been doing it since 2009, which means I’m somewhere over the million-word mark. But those compelled to write will never be satisfied with just that. One does not live by blog alone, after all.

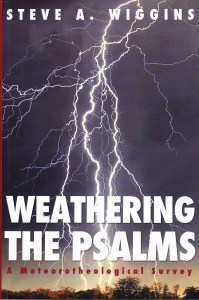

Once in a great while I get asked how many books I’ve written. Well, that’s not a question with a straightforward answer. Two of my books have been published. I’ve written at least ten. Some of them never made it from my desk to a publisher’s wastebasket. A few of them have. Like others who are addicted to writing, I can’t stop. Ironically, with a decade of experience working in publishing I’m not so good at getting my own work placed. Some of it is fiction. Some of it is non. Some of it is even poetry. If you’re a graphomaniac, I don’t need to explain any further. If you’re not, think of chocolate, or sports, or anything else you just can’t get enough of. That’s what it’s like.

Shapiro’s book, although not point-for-point, but more than not, is like wandering through my own gray matter. I had no idea that other writers—including a successful one like Shapiro—felt the same constant, nagging doubts and insecurities. I didn’t know that others considered staring off into the middle distance (there’s not always a window nearby) as work. Or that sometimes you write something and when you’ve finished it seems like it wasn’t you at all. Writers can be a trying lot. We tend to be introverts. We have odd habits (in my case, waking up at 3 a.m. to write on a daily basis). We tend to be able to spot one another in a crowd, but more likely as not we won’t say anything to each other. And strangely, we write even if we don’t get paid. With lifelong royalties somewhere in the low triple digits, economically it makes no sense to do what I do. Generally the world feels creative sorts aren’t terribly productive. It’s because we measure value differently, I expect. I’m glad to have met another traveler on this path although, as is often the case, our meeting will only be through writing.