Toothbrush and dental pick in hand, I go at it. Not that I’m a professional, mind you, but curiosity drives me to this. You see, this crinoid before me is at least 358 million years old and anything that can make me feel young deserves all the attention I can give it. Crinoids are also know as “sea lilies,” but they aren’t plants. They’re actually echinoderms, and the fossils I’ve found in the past have only been cross-sections of their “stems,” a stone circle, as it were. This one has tendrils visible, and I can’t believe that it was a chance find on one of my recent walks through Ithaca’s gorges. I’m dreaming Devonian dreams, and I want to brush away the plaque of the eons and see what I’ve actually found.

Fossils are a kind of eternal life. The creature that died to leave this impression lives on as a monument in stone. It reminds me of my unfortunately brief stint as an archaeological volunteer. Scraping away dirt to reveal a piece of pottery that hadn’t been touched by human hands for 3,000 years. Of course, that’s merely a second ago when you’re talking about something pre-Carboniferous. The dinosaurs won’t even show up for another 100-million years. And I think I have to wait too long for the bus. Time, as they say, is relative. Did this medusaized creature before me realize just how terribly long it would take for enlightenment to arrive? And how so very swiftly it could fall one foolish November night? Careful, this fossil’s fragile.

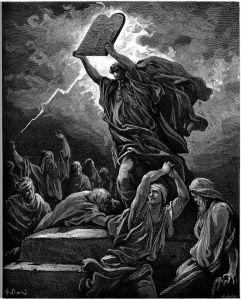

I grew up among the Devonian substrate in western Pennsylvania. The Bible on my shelf told me to disregard the evidence before my eyes. Some clever true believer had declared Noah’s flood the culprit, never bothering to explain how freshwater fish showed up after the deluge. Those we tried to keep in our aquarium never seemed to handle the slightest disturbance of their salinity. The ages of the literalist are by definition short-sighted. 6,000 years seems hardly enough time to account for any sedimentary stone, let alone that riddled with fossils. I’m hunched over my bit of slate, dental pick hovering nervously over what will never come again. The Bible behind me says it’s an illusion. You may be right, Mr. Scofield. You may never have evolved. But as my fingers glance a creature dead before even the crocodile’s grin I have to declare that I have.