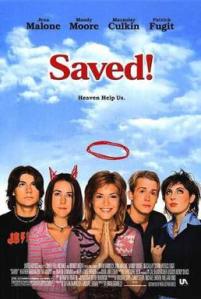

One of the many questions that haunt evangelical Christians is whether it is okay to watch horror films or not. The same applies to whether it’s okay to listen to rock-n-roll (even as it’s reaching its senior years). Cultural accommodation is often seen as evil and evangelicalism, as a movement, is frequently offered as a culture all its own. I recently rewatched Brian Dannelly’s Saved!, a coming-of-age comedy about a group of teenagers at American Eagle Christian High School. Gently satirical, it portrays well how evangelicals try to redefine “cool” in a Christian mode. Taking tropes from pop culture and “baptizing” them, Pastor Skip—the principal—assures the young people that they’re every bit as cool as secular culture icons, only the Christians are going to heaven.

The film came out when I was teaching at Nashotah House. That seminary also had problems with secular culture, but in a completely different way. Its method was basically to ignore that culture. Isolated, Anglo-Catholic, one might even say “Medieval” but for the sanitation, it was likely not a safe place for a professor to be watching such films. Evangelicalism and right-wing Catholicism were beginning to find each other. Once the cats and dogs of the theological world, they were becoming more like goldfish in their bowl, watching a strange and unnerving world just outside the glass. A world in which they couldn’t survive. Now, Saved! is only a cinematic version of this, but it has a few profound moments. Mary, the protagonist, comes to see the hypocrisy of both the school and her former friends when she supports a boyfriend who is gay.

At one point her friends attempt an intervention. They try to exorcize Mary, and when that fails one of them throws a Bible at her. Picking it up, Mary says “This is not a weapon.” Since this movie isn’t by any stretch of the imagination horror, I didn’t address it in Holy Horror. As I rewatched it in the light of that book, however, I recognized a motif I did discuss in it. The use of the Bible in movies is extremely common. That applies to films that don’t have an overt Christian setting such as this one does. The iconic Bible is a protean book. Despite what Mary says it can indeed be a weapon. It often is. Many of us have been harmed by it. Christian separatist culture has its own dark side, even if it’s carefully hidden, its adherents think, from the secular world outside the fishbowl.