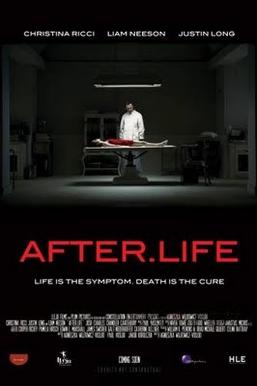

Depending on who you are the Bigelow Institute for Consciousness Studies (BICS) may set your eyeballs to rolling. You might know that extremely wealthy Robert T. Bigelow made his fortune as a hotelier and then began investing his money in aerospace technology. He publicly admits to believing that aliens are already among us, and has contributed to advances in space travel components. (It seems that many of the uber-wealthy are looking for a way off this planet at the moment.) Not an academic, Bigelow is keen to admit his interest in what is often laughingly labeled the “paranormal.” If you’ve got money you really don’t need to worry about what other people say. I recently ran across an announcement regarding the winners of a BICS essay contest regarding the survival of consciousness after death.

As I’ve noted before on this blog, the paranormal and religion are close kin. Nevertheless it does me good to see that so many people with doctorates (both medical and of philosophy) entered the contest. I’m glad to see not everyone is buying the materialist narrative. We’ve been so misguided by Occam’s razor that we can’t see reality is more complex than they teach us in school. Churches may not be doing it for us any more, but it does seem that “there’s something out there.” With a top prize of a half-a-million dollars, there was certainly a lot of interest in this enterprise. If you go to the website you can download the winning papers.

Consciousness remains one of the great unexplaineds of science. Answers such as “it’s a by-product of electro-chemical activity in the brain” don’t mesh with our actual experience of it. Indeed, we deny consciousness to animals because our scientific establishment grew out of a biblically based worldview. Even a century-and-a-half of knowing that we evolved hasn’t displaced the Bible’s idea that we are somehow special. Looking out my window at birds it’s pretty clear that they’re thinking, solving problems. Dogs clearly know when they’re pretending, as in a tug-of-war with its weak owner. We don’t like to share, however. Being in the midst of my own book project I really haven’t had time to read the essays yet. I do hope they come out in book form, even though they’re now available for free. I still seem to be able to carve out time for a book, which is something I consciously do. I’m not convinced by the materialist creed, although I’ve been tempted by it now and again. I like to think that if I had money I’d spend it trying to sort out the bigger issues of life, no matter what people call them.