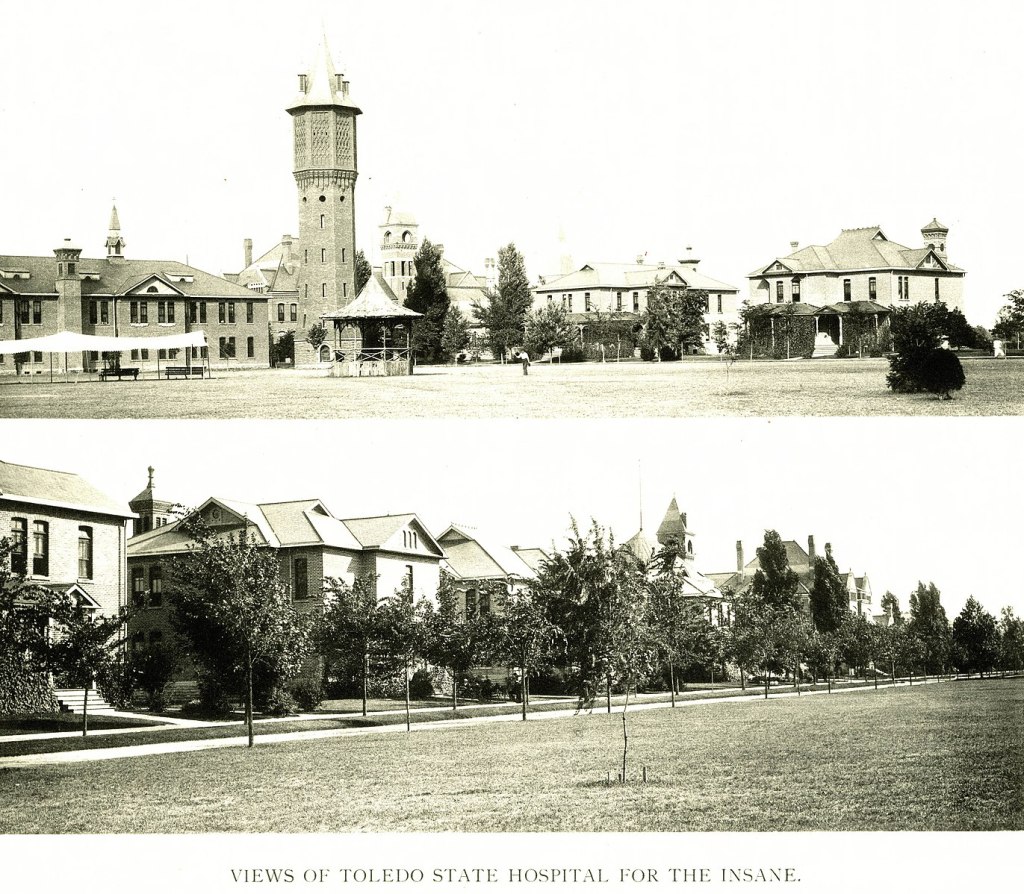

I was reading, as one does, about a mental institution. In the last century they were often called, rather insensitively, “lunatic asylums.” The neurodiverse were often shunted away so that the rest of society could get on with business as usual (as if that’s sane). There were any number of reasons sought for such individuals thinking differently. The source I was reading had a short list and I was surprised to see on it, “over study of religion.” It really said nothing more about it but it left me wondering. First of all, it brought Acts 26.24 to mind: “Paul, thou art beside thyself; much learning doth make thee mad!” Religion, from the very start, it seems, had the reputation of driving people insane.

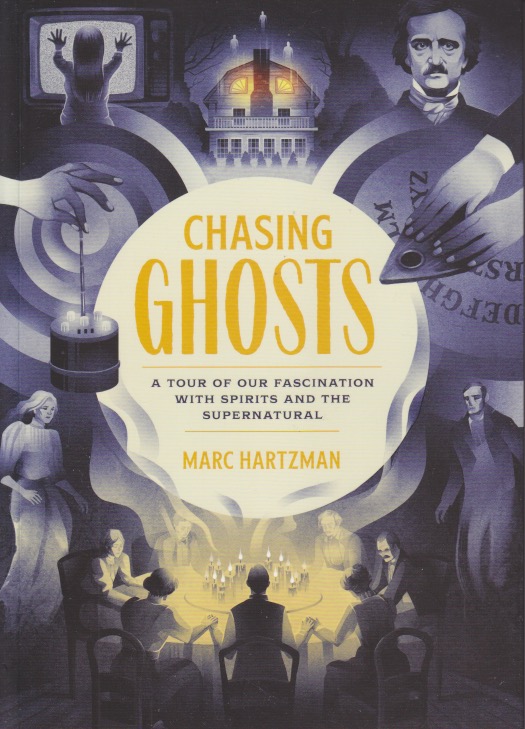

As someone who’s spent well over half a century thinking about religion, reading about religion, and analyzing religion, I can see Festus might’ve had a point. This way much madness lies. I don’t think religion evolved to be thought about. It was largely a fear reaction to being, in reality, rather helpless in a world full of predators and other natural dangers. Although we’ve managed to wipe out most of our large predators, we’re still under the weather, as it were. We can’t control it, and what messing around we’ve done through global warming has made it less hospitable to our species and several others. And also the small predators, those that evolve quickly, such as Covid-19, are now the real challenge. Facing fear was the real evolutionary advantage of religion.

Being story-telling creatures, we made narratives about our belief systems. Then we started taking those stories literally. Believing too seriously, we used those stories as a basis for hating and killing those with different stories. We still do. Can anyone deny Festus’ accusation? I’m sure religious mania has, historically, led to some institutionalizations. It was kind of a trope in the seventies, for example, that too much Bible-reading could lead to criminal behavior. It’s not difficult to see why those trying to classify what might make an individual off balance might look to religion as an explanation. Nationally, and very publicly, we can see strident examples of this promotion of irrational ideas on a daily basis. Many of the large mental institutions have been closed down and many of the neurodiverse have been turned out to the streets. Ironically, it is often the religious who try to care for them. Understanding religion, it seems to me, might be a great public good.