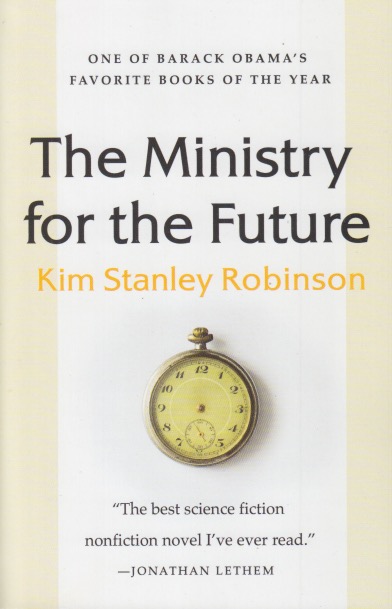

I’ve been on the Green Committee at work almost since I started the job. Occasionally for Earth Day we’ll have a book discussion. Usually it revolves around nonfiction books that my press publishes. This year they selected Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future. It’s an environmentalism tale of what global warming may well be like and the political machinations it might take (and the millions of deaths along the way) before we stop burning carbon. It’s a long and detailed and political story. Robinson is known as an intellectual science fiction writer and there are sci-fi elements to the book, but its style is realist and its outlook, while ultimately hopeful, is staid. Even when humans start to move in the right direction. It’s also a very long book.

Reading it got me to thinking again of a somewhat bewildering truth: environmentalism books tend not to sell overly well and sustained reading, even by supporters, is difficult. Many of us know that we’re beyond the tipping point for environmental disaster. The Trump years assured us that it is coming. One of the elements Robinson makes clear is just how politically entrenched it is. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons for the despair. The vast majority of people in the world want a more environmentally conscious government, but plutocracy tends to bring narcissists to the top and the needs of all others are less important. In Robinson’s version of the story, targeted violence is the only thing that works. Near the end of the story an interesting idea is raised: the Ministry of the Future (which is a government ministry, not the church kind) concludes a new religion is needed.

The masses of people, you see, are followers. Religious leaders reinforce the idea that God told their founders—and by extension their followers—the only truth. Their jobs (and ministries are jobs) include reinforcing those ideas to people who’ve been raised or converted to that particular brand of religion. A number of New Religious Movements, and even a couple of prescient ancient religions, have been purposely constructed. The trick is to get followers to accept that the religion is legitimate. Most western religions around today have been based on the idea that humans can do whatever they want with the planet—even destroy it to force God to return. I kind of like Robinson’s idea better. Perhaps that’s why religions form around movies like Avatar. Not a bad thought, when your job has you reading a sci-fi novel. A religion saving the earth feels like a novel idea.