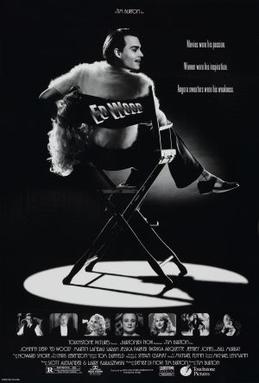

Most of us know a bad movie when we see it. Some of us walk away. The rest of us linger and wonder. Some weeks ago now I watched Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space. “So bad that it’s good” is the mantra often chanted about it. I lingered because of Ed Wood. While it’s somewhat fictionalized, Tim Burton’s Ed Wood is itself an odd movie. It performed poorly for a Burton film starring Johnny Depp. Critically, however, it was praised and it eventually became a cult film about a cult film. Or films. Mainly, I suspect, because Ed Wood is such an interesting figure. He was a man who wanted to make movies—knew he was meant to make movies—but never got the backing he needed to make them. He did it anyhow.

Ed Wood starts with Glen or Glenda. Written and directed by Wood, who also starred in it, this movie was about cross-dressing. In real life Wood’s mother used to dress him up as a girl and although he was heterosexual, Wood became a transvestite. This was, of course, in the days when such a thing was scandalous. Making all of this surreal, and poignant, Wood had befriended an unemployable Bela Lugosi—known to be a drug addict—and had him star as God in the movie. The next film Ed Wood focuses on is Bride of the Monster. Again starring Lugosi, this one has a giant octopus in it and heads toward horror territory. The film about a filmmaker ends with his notorious Plan 9 from Outer Space, the last film in which Lugosi appears and which was financed by a Baptist church.

Ed Wood ends before Wood becomes a poverty-stricken alcoholic and dies in his fifties. There is a poignancy both to the stories of Wood and Lugosi that also applies to many people in life. People who know, without a doubt, what they should be doing with their time on earth but who are kept from it by those, who like Lugosi’s God, pull the strings. We all have limited time and as we grow older we realize that spending it doing a job that’s a drudgery is really a kind of crime. Would Ed Wood have become a famous director if he’d been backed by the money to produce the movies he wanted to? We have no way of knowing. What we do have, however, is a tribute by a talented film maker to a fallen colleague, and that, it seems is the best part of human nature.