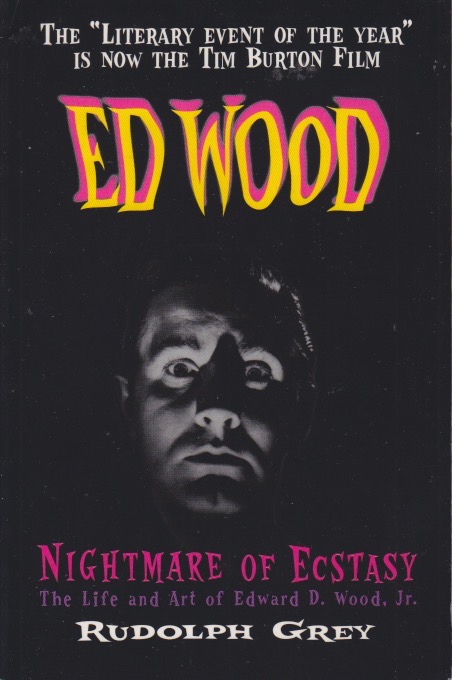

Fandom can lead to fame, even if it’s just cult fandom. The nature of Ed Wood’s films is such that he could’ve been among those forgotten had he not posthumously developed a following. Unfortunately it didn’t arise in time to ameliorate the tragic final years of his life when he died pretty much penniless, drinking away the pain. Rudolph Grey’s Nightmare of Ecstasy: The Life and Work of Edward D. Wood, Jr. may have helped rescue him from obscurity. Of course, Wood had gained a following earlier than the book, but nobody had really thought to document his life. What I find so compelling is that Wood was like so many of us—trying hard to gain some recognition only to be shut out of what we love by a huge industry that calls the shots. It’s difficult to get notice as an independent filmmaker, or even as a writer publishing with smaller presses.

Wood lived a most unusual life. A straight transvestite, he fought as a Marine in World War Two. He moved to California to try to break into filmmaking and wrote and directed several movies. When this failed to make enough money to support him, he turned to writing pornographic novels and film scripts. Wood had, interestingly, befriended a lonely and washed up Bela Lugosi. His last two movies were Wood’s work. Wood found camaraderie with other outsiders in Hollywood and he cast them in his low-budget productions. He would try to shoot his films in less than a week. Considering the constraints under which he operated, his movies really aren’t that bad. They aren’t good by conventional standards, but they’re better than many other people could’ve made them in his circumstances.

This book isn’t a conventional biography. There’s no narrative apart from the recollections culled from interviews of those who knew him and occasional letters and writings of Wood himself. As with any biography there are gaps and lacunae. From a writer’s point of view perhaps the saddest part of the story is how Wood and his wife were evicted from their final apartment and he had to leave his papers and manuscripts behind. These were reportedly thrown into a dumpster and lost forever. Although his movies may have been bad, Wood was a capable writer. And like any writer he felt the loss of his work keenly. He only lived about three more days after that. His friends had largely abandoned him, alienated by his drinking and its effects on him. Next year will mark the fiftieth anniversary of his death and, I hope, the commemorative watching of some bad movies that deserve to be remembered.