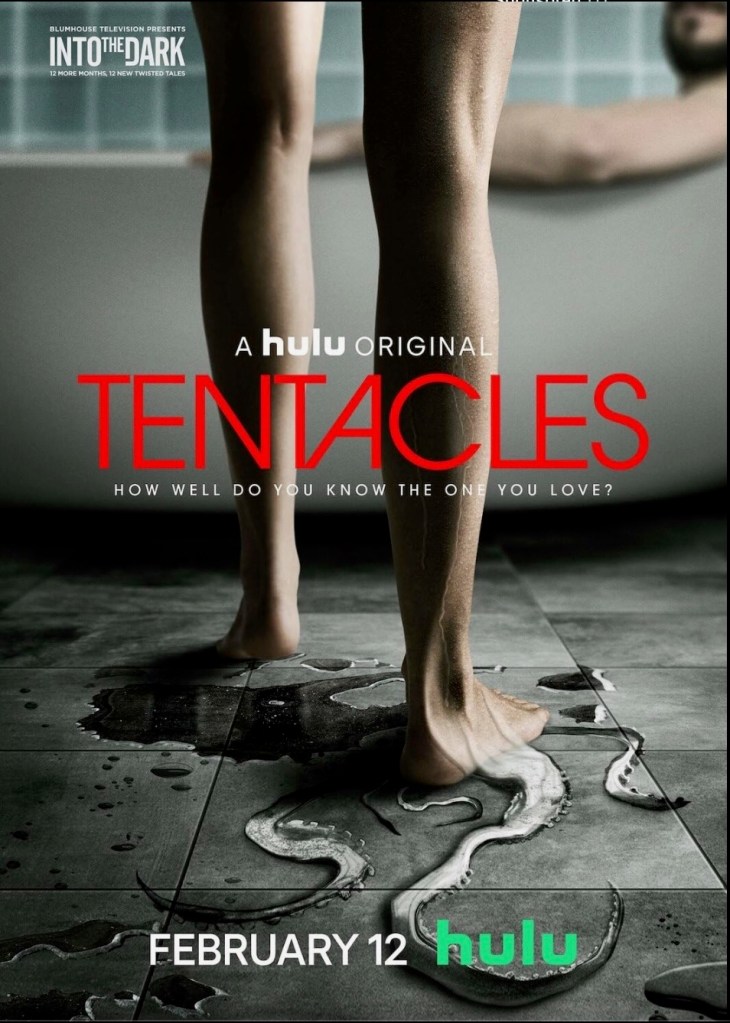

I was attracted to the Lovecraftian aspect of the title. Of Tentacles, I mean. I wasn’t aware that Into the Dark was a Hulu series of television shows based on holiday horror. I watched Pure without realizing that. Movies these days are complicated. In any case, Tentacles caught my attention and although it isn’t a tier-one horror film, it’s fun in its own way. Tara, a desperate young woman, is looking to buy a house. She finds Sam, who’s trying to sell his parents’ place and seduces him into letting her renovate it. The two fall in love and Tara reveals she’s being stalked by an ex. Sam has, however, come down with an illness that doctors can’t identify. Something is putting tentacles into his ears as he sleeps. It doesn’t take long to figure out that Tara’s not what she claims to be. She’s some kind of creature that originated in the ocean, but survives on land by taking part of her victims and slowly becoming their double. The original, of course, must be disposed of.

This is a serviceable little movie. The acting is good, particularly on Tara’s part. There’s enough mystery and energy to keep viewers engaged, despite the commercials. It also made me realize that Into the Dark might be worth exploring a little more intentionally. When I went to my usual places to find out more about what I’d just watched, it was a little tricky. To find the write-up on IMDb you needed to find the series title first so that you could click onto the individual episode. This is so different than either the major studios or independent filmmakers. Streaming services, however, have been offering some good home-grown horror. I’ve seen some notable examples from Netflix, Amazon, and, of course, Hulu.

Anything with tentacles seems to have a tangible Lovecraft connection these days. In large part it seems to be because of the internet success of Cthulhu. Those who spend lots of time online know who the Old One is without having ever read H. P. or having watched horror. He’s become the monster with tentacles, something my college sci-fi professor would doubtlessly have commented upon. Lovecraft himself would have, I suspect, enjoyed the notoriety but would likely have felt some disappointment regarding the point he was trying to get across. (That’s more evident in Older Gods.) The vacuousness of being alone in a meaningless universe was more his aesthetic. Still, it inspired some fun films for a sleepy weekend afternoon, and its tentacles keep on reaching.