October, well September and October—actually June through October, took many unexpected twists this year. I’ve had to lean heavily on Halloween spirituality to make it through. That’s good because we haven’t had time to decorate for the holiday. We haven’t had time to get out just to appreciate the leaves, to go to a farm for pumpkins, let alone carve any. Or come up with a costume. I couldn’t even get to the theater to see The Nun II, despite having written an article on the universe to which it belongs. Halloween spirituality works in times of less-than-optimal circumstances. Anyone who reads this blog more than once or twice knows that struggle is a fairly constant theme. Halloween spirituality comes to those who need it, and it helps us to get through.

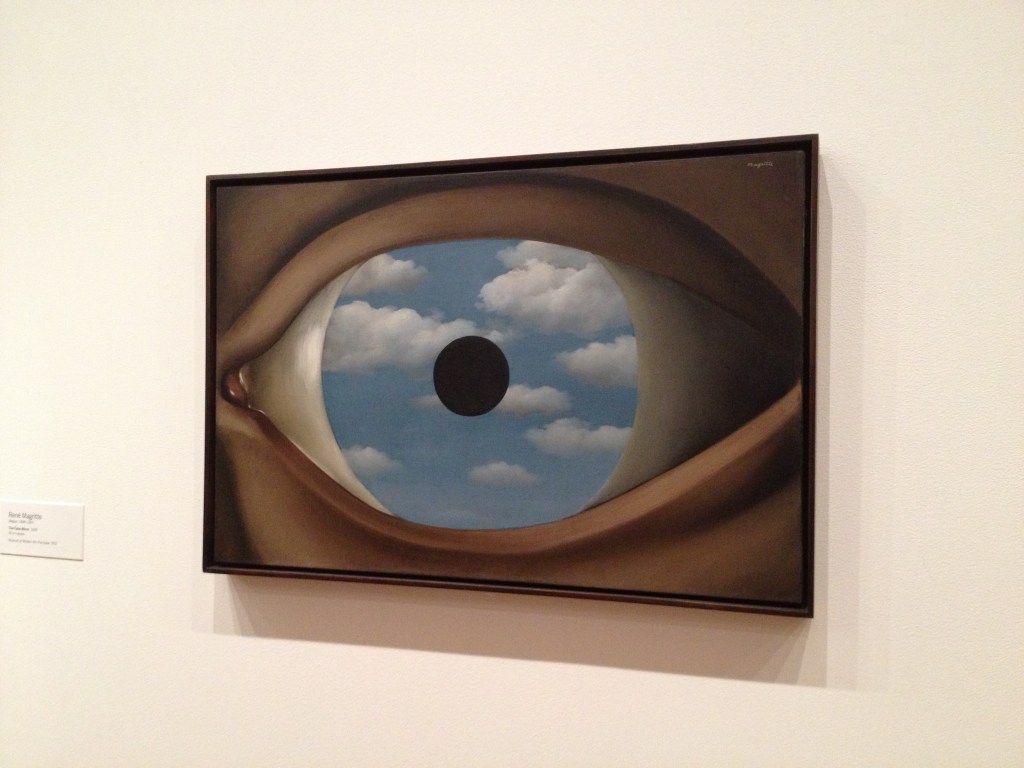

With the death of my mother this month, I’ve been thinking a lot about family. My family is where my spirituality began. I’ve been haunted by the truth since I was a child. I need to know what’s true. It’s one of the few non-negotiables in my life. Halloween is true because it’s honest. We wear masks, but we do so all the time. On Halloween we have the courage to admit it. Some of us are scared little boys or girls inside, trying to find meaning in a world that makes no sense. A world that is run by the ambitious and greedy—those who are powerful because others fear them (Halloween is honest, my friend)—and who make rules by which the rest of us must live. Halloween says it’s all right to be scared. Yes, the monsters are real. And most of them would treat you far better than you might expect. Trick or treat.

Halloween spirituality is about hope. It’s a pivot point around which the year revolves. I look forward to it each year once it has too swiftly passed. In the slow change of progress, I hope that it will eventually be recognized as a national holiday. I find the holidays a season of hope. For me that season begins with Halloween. From here it’s almost possible to see Thanksgiving and from there Christmas isn’t far off. I save vacation days to be able to take a mini semester break—something in every teacher’s blood—that allows me to reboot. Halloween spirituality is one that anticipates rest and quietness, celebration and reflection. It’s a time when busyness must wait its turn. When the dark is allowed to utter its peaceful sighs into a world where too much is happening all the time. By the way, I decided on my Halloween costume: AI, disguised as a human being.