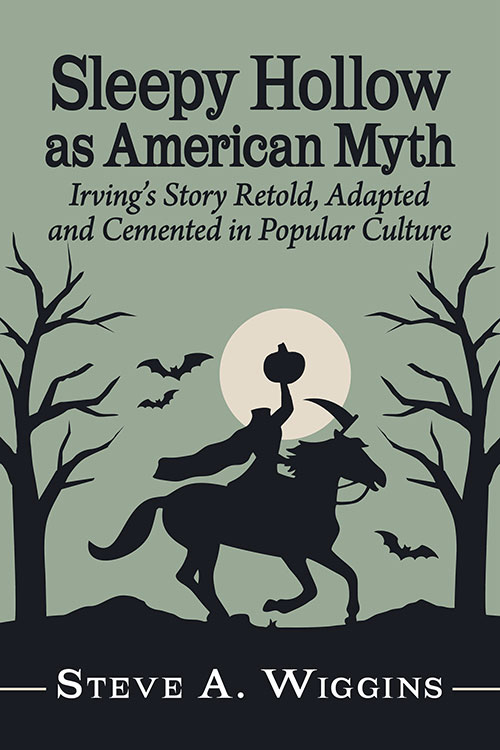

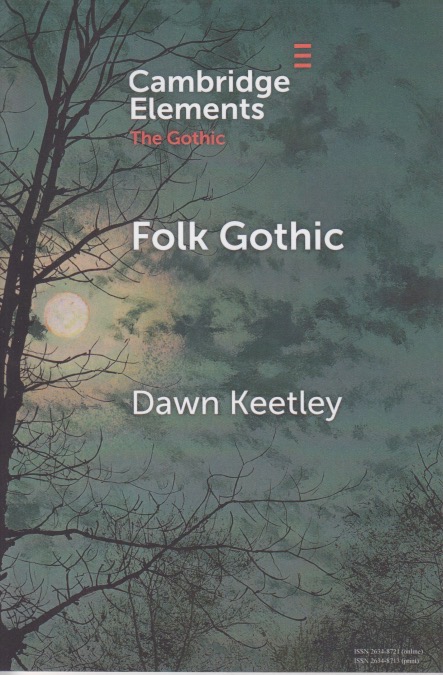

One of the many peculiarities of my thought process is that I’ve tried to discuss only “whole pieces” on this blog. In other words, as a “consumer” of media, my self-imposed limit has been discussing only whole books rather than a single short story. Or the entire run of a television series rather than an individual episode. The startling contradiction occurred to me that my latest book is an extended study of a single short story. You see, Washington Irving was no novelist. As America’s first famous writer, his fiction came in the form of short stories—sketches, he called them—and so to write a book on Sleepy Hollow meant focusing on a short story. I love to read short stories. I’ve always waited to talk about them here after finishing the book I found them in. Maybe it’s time to discuss stories, or individual episodes here as well.

“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” many people are surprised to learn, is not a novel. It’s often presented that way in telinematic adaptations. The story, published as part of a collection of stories in 1820, is only 12,000 words in length. Now, if you don’t work in publishing that figure may mean nothing to you. There is no scientific way to parse these things but short stories tend to run from a few hundred words to about 15,000. The next major category, the novella, is generally said to start at about 17,500. You’ll notice there’s a gap there, between the two. This is the strange territory sometimes called the “novelette.” That’s because many modern fiction publishers cut the short story off at 7,500 words, and that leaves a gap of a literal myriad of words. 7,501 to 17,500 is the novelette, according to some. And for the sake of completion, the novella tops out at 40,000 words so anything longer is a novel.

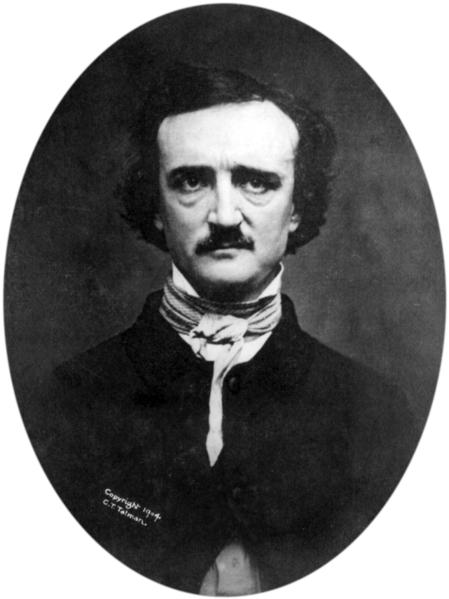

Irving wrote before these fine distinctions existed. He wrote and people read. Poe fell into a similar category. He was known to have written only one novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, but some of his short stories are long. “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall” stops just shy of 19,000 words, a novelette in today’s nomenclature. My own fiction writing has been shaped by the fact that many magazines (even online, non-paying) top stories out at 5,000 words. Some even at 3,000. If you’ve ever tried to get a novella published, you’ll know why you shouldn’t even try. All of which is to say maybe it’s time I start giving myself a break and talk about short stories. Or an interesting episode. If I can wrap my brain around it.