He was probably trying to impress his wife with his wit. I was in a department store—a rarity for me. I was wearing a mask, because, well, Covid. As this guy, older than me, walked by he said “Halloween’s over. Take off your mask.” It bothers me how politicized healthcare has become, but what bothered me more was that it was only October 20. It wouldn’t even be Halloween for another 11 days. What had happened to make someone think Halloween was over so early? Yes, stores had switched over to Christmas stuff by then. In fact, I wandered into another store where Christmas carols were playing. Capitalism seems to have wrenched the calendar out of order. We’re tired of All Hallows Eve before it starts. In fact, just the day before we’d gone out to a pumpkin patch to get our goods and the carved pumpkins are now showing their age.

If that little exchange in the store had been in a movie, it would’ve been a cue for me to transform into some big, scary monster. Of course, Halloween is what it is today because of relentless marketing. And a handful of nostalgia from people my age with fond childhood memories of the day. For some of us, however, it is a meaningful holiday in its own right. It makes us feel good, even after we’ve grown out of our taste for candy. It is significant. Christmas is a bit different, I suppose, in that there is nothing bigger following, not until next Halloween. Besides, Christmas is supposed to go for twelve days. The fact that Halloween is a work day makes it all the more remarkable. We have to work all of this out while still punching the clock.

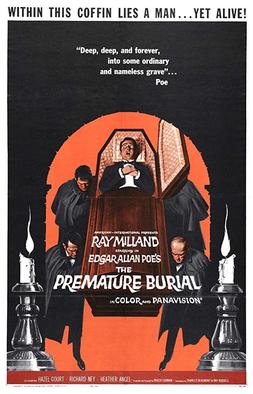

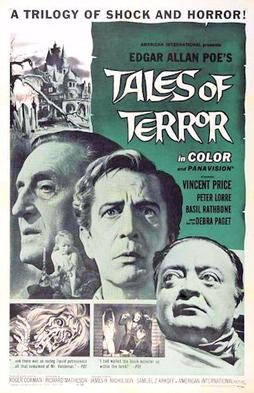

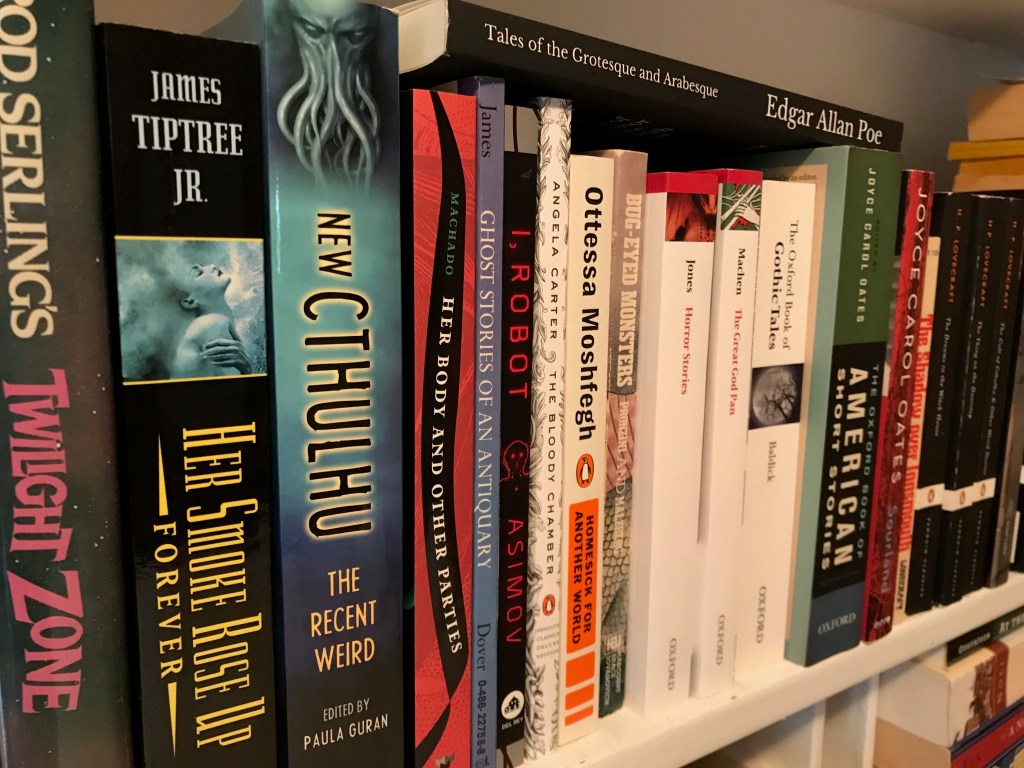

I had really hoped to be able to get to Sleepy Hollow this Halloween. Sleepy Hollow as American Myth tries to make the case of how that story and Halloween came of age together. It is the iconic Halloween story, what with ghosts and pumpkins and all. And the month of October is spent with scary movies for many people. This month I’ve posted about horror movies every other day, pretty much, trying to connect with my audience. If that is my audience. I tend to think of Halloween as a community. Those of us who, for whatever reason, think of this as our favorite time of year. A time when perhaps we don’t feel so stigmatized for liking what we do. A time that we’re not hoping will shortly end so we can get onto the next thing. It may have been meant as a joke, but I wasn’t laughing. Happy Halloween!