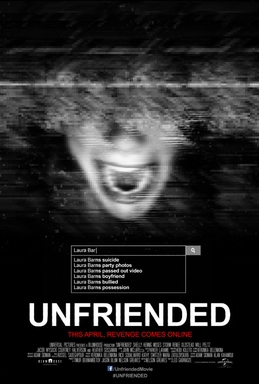

A ghost-revenge story, online. Unfriended is one of those low-budget horror films that manages to be remarkably effective through the acting and its overall verisimilitude. It’s also a kind of parable about the dangers of living our lives online. The only problem is that technology is moving so fast that a ten-year old movie looks outdated. The scary thing is many people are online even more, especially since the pandemic that came a few years after the movie was released. Six high-schoolers are chatting on Skype (see what I mean?). A friend in the group died by suicide a year ago because of an embarrassing video posted of her on YouTube. Even a mature viewer like me can easily recall how deeply peer pressure cut in high school. It’s a difficult time for all of us. In any case, an unidentified person has joined the call and makes threatening comments via chat.

Of course, there are multiple apps (we called them programs long ago) running and nearly the entire movie is on the screen of one of the kids’ laptops. In real life I was waiting for my low battery warning to come on, because I was watching it on a laptop, and all the notices that appeared on the upper right-hand corner made the thing look real. Naturally enough, the kids start getting killed off. Since this is horror their deaths are shown, if briefly, on screen and mostly they’re bizarre. Hovering in the background is a webpage that warns against opening and answering messages from the dead. As Blaire (whose screen we’re seeing) comes to realize that the unknown person is the girl who died by suicide, Laura (the dead friend) forces them to play a game of Never Have I Ever. This leads to dissension and fighting as confessions come out and friends begin dying.

There’s a heavy moral element involved—the teens are being “punished” for typical teen behaviors. Interestingly, toward the end I noticed that Blaire had a crucifix on her bedroom wall. The kids don’t talk about religion at all (something I did do as a teen) but they all have a moral sense of what they did wrong. The webpage about not answering online messages from the dead suggests confessing your sins, if you do open such a message. Blaire tries to confess, but she has a secret that’s kept until the very end, so I can’t say what it is here. I wouldn’t want to be unfriended for providing a spoiler.