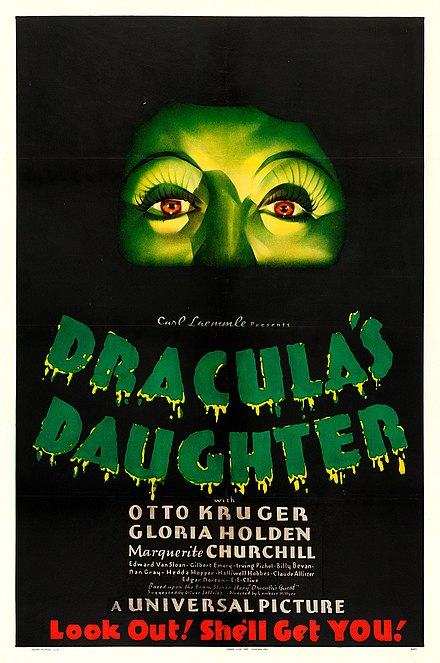

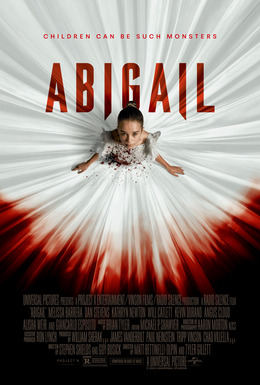

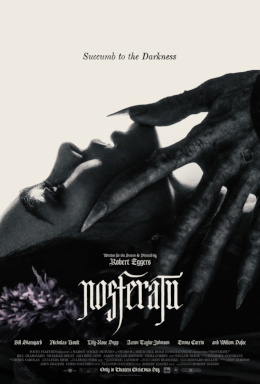

Nosferatu, by F. W. Murnau, was deemed in copyright violation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and ordered destroyed. Rights to the novel were properly purchased by Universal and the horror film proper was born. Other studios wanted to get in on the action, so the rights to the story of the Count’s daughter were bought by MGM. They then sold the rights to Universal so that the latter could produce a sequel to their earlier hit. Dracula’s Daughter didn’t do as well as the original, but it kept the vampires coming. Some years later, Son of Dracula came out, keeping it in the family. Having watched Abigail, I had to go back to Dracula’s Daughter to remind myself of how the story went. I recalled, from my previous watching, that it wasn’t exactly action-packed, but beyond that thoughts were hazy.

Picking up where Dracula left off, von Helsing (that’s not a typo) is arrested for staking a man. Then a mysterious woman arrives and steals the body to destroy it in an attempt to rid herself of vampirism. We see that just five years after Dracula the reluctant vampire was born. Creating a scandal at the time, Dracula’s daughter also seemed to prefer females. Apparently the script was rewritten several times to meet the approval of censors during the Code era. The modern assessment is that this is based more on Sheridan Le Fanu’s Camilla rather than an excised chapter of Bram Stoker’s novel. Since the world wasn’t ready for lesbian vampires in the thirties, she falls for Dr. Garth, a psychologist that she wants to live with her forever. Kidnapping his secretary to Transylvania, she draws him to Castle Dracula. Her jealous servant Sandor, however, shoots her with an arrow. Von Helsing explains that any wooden shaft through the heart will do.

Already as early as Stoker, at least, Dracula had brides who were vampires. It makes sense that there might be daughters and sons. And studios, learning that people would pay to watch vampires on the silver screen, were glad to keep the family dynamics rolling. Vampires proved extremely popular with viewers—a fascination that has hardly slowed down since the horror genre first began. Some of the more recent productions explore themes and approaches that simply wouldn’t have been possible in the early days of cinema. We don’t see Dracula’s daughter actually biting victims—one of the many things the Production Code wouldn’t allow—and there’s no blood. Nevertheless, the story itself went on to have children and they are still among us.