The Dead Sea Scrolls are coming to Times Square. Times Square is the kind of place where you know your being sworn at, but you’re never really sure in what language. It is a place of the people. So the sacred meets the profane. Mircea Eliade would be scratching his great head with his pipe firmly in hand. The Dead Sea Scrolls are the sexiest of ancient documents. Their story has it all: mystery, intrigue, conspiracy, romance—well, maybe not romance. A chance discovery by dirt-poor Bedouin in a desert, ads being taken out in the Wall Street Journal, clandestine meetings with ancient texts being viewed through a hurricane fence in a forbidden zone. And do those scrolls ever get around! I first saw them (those that are accessible to the public) in Jerusalem. The next time was in the Field Museum in Chicago. Now I’m feeling a bit blasé about the whole thing.

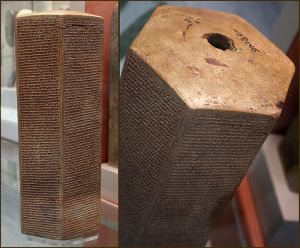

Those of use who’ve spent much time (too much time) with ancient documents relating to the Bible know that the Dead Sea Scrolls require no introduction. The far more interesting (and sexy–yes, literally sexy) Ugaritic tablets still receive slack-jawed stares of unrecognition, despite their importance. Those who read the stories of Baal, Anat, El and Asherah wonder why the “Classics” only begin with Homer. People have been creative with the gods since writing began. The theme of the human race might be summed up as, “if the gods are so powerful, what am I doing in a dump like this?” Fill in the blanks—that’s religion. From the beginning, once we’d come up with gods, we began to wonder why they treat us so. People are on the receiving end and so many things can put gods into a bad mood. It’s your basic dysfunctional family.

No doubt the Dead Sea Scrolls are important. We have learned much about the context of early Christianities from them. They provide the earliest manuscript evidence for the Hebrew Bible. And they’ve got that Dead Sea mystique. When I read the story of their discovery, I understand why crowds will flock into a tight room to stare through the glass at a bit of shriveled parchment that most of them cannot read. It’s like standing next to someone famous and powerful; maybe Moses or King David. Or more famous and powerful, like George W. Bush. I know, that was the last administration. But the Scrolls come from an even earlier one. I just hope somebody will give me a call when they find one that tells what happens when Baal meets Astarte. That will be worth the price of admission! And, who knows? It might even fit in with the spirit of Times Square (pre-Disney, of course.)