This is one of my favorite doodles from the ancient world. Its rich ambiguity lends to its appeal — some see it as salacious, while others see it as sacred. For those of you unfamiliar with the graphic details of the Asherah debate, this image is an ancient graffito from a desert way-station called Kuntillet Ajrud, a one-period site from the eighth century BCE. Like any number of other ancient drawings, this one would have probably remained in the obscure curios-portfolio of ancient scholars if it hadn’t overlapped an inscription that mentions “Yahweh of Samaria and his asherah.” Discovered in 1975–1976, this inscription, along with a couple others, revolutionized many scholarly assessments of ancient Israel’s religion. Yahweh had a soft side after all, a wife no less, the old god!

I’ve taken some flak in my circumscribed academic career for suggesting that this inscription, and a perhaps somewhat similar one from Khirbet el-Qom, are ambiguous. Sure, I’d like to see Yahweh happily married as much as the next guy, but is that what is going on here? Yahweh and Asherah, sittin’ in a tree? My doubts don’t stem from a squeamish conservatism (come on!) but from a concern of over-interpreting ambiguous evidence. Asherah, as a goddess, was rediscovered with the excavation of Ugarit. Forgotten by time with only cryptic references in the Hebrew Bible to some kind of cultic item called an “asherah,” scholars were excited to learn that she had a body and a personality. Many aspects of that personality fit, circumstantially, with a lovely pairing with Yahweh; wherever Asherah appears she is the consort of the high god, she is royal, matronly, and never showy.

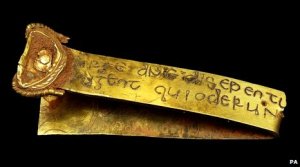

The image above, however, has nothing to do with the inscription it overlaps. The two larger figures in the foreground are clearly Bes, the minor Egyptian protective deity. The characteristics are so clichéd that only the will to see Yahweh and Asherah arm-in-arm suggests anything different. Scholars like a happy ending just as much as anybody else, but I am obligated to state that, taken objectively, Asherah simply isn’t in the picture here.