I don’t know much about the music industry, but I do know that as in publishing, labels make a difference. Who doesn’t conjure up a certain sound when they see Motown? Companies jealously sign artists to their label, with a close eye on the bottom line. Labels. Branding. Marking our territory. People like to give things labels to make them easier to understand. By now it’s no longer news that David Bowie has died. The tributes are coming thick and fast, and one recurring theme seems to be that nobody really knew how to label him. Bowie was an original, a creator. Like many truly creative people, he was seldom at the top of the charts, but his fan-base grew over decades and those who listened to him knew that he defied labels. Labels are for convenience, and life is, well, not convenient.

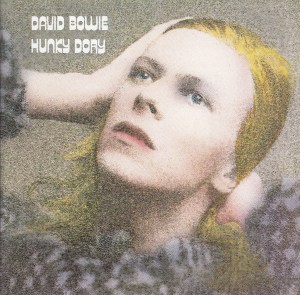

There’s been speculation about his final album, Blackstar, released an iconic two days before his death. The song “Lazarus” has flagged the attention of many, but here we are after the third day and he hasn’t come back. I think of my childhood and tween years in the 1970s, seeing Bowie’s album covers in my brother’s room and wondering if he was a man or woman. His transgressions frightened the young conservative that I was, accepting the label given to me by those who thought they knew me. I heard his songs coming through the open door. I couldn’t understand them, but somehow they remained with me until I was mature enough to learn to listen. Some sounds are too subtle to hear, except with experience. Here was a man telling the world “don’t label me.” And yet label we did.

“Lazarus” is a haunting song. I may be no music critic, but here is a piece by a man who knows he’s dying. The video shows him emerging from a tomb-like wardrobe (in itself significant) and simultaneously lying on his deathbed. He’s in Heaven, but in danger. Still, he knows he’s free. Like the biblical Lazarus from the Gospel of John, resurrection is only temporary. Lazarus has come back, but he must die again. As the frantic Bowie scribbles his final words on the final page, he backs up once again into the tomb from which he emerged. David Bowie may not have been a Bible scholar, but his song is prophetic. The three days have now gone past. He may not have come back, but it just may be that he never really left.