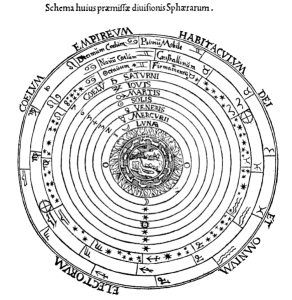

What could be more humbling than living in an infinite but expanding universe? Since the days of Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton we’ve known that the apparent reality of both our own lives and that portrayed in Holy Writ is inaccurate. The earth doesn’t hold still, and the sun doesn’t rise or set. The universe isn’t a layer-cake with Heaven above and Hell beneath. Instead it’s mind-numbingly massive. The only appropriate response, it would seem, would be silent awe. Marcelo Gleiser, whose work I’ve mentioned before, is a rare scientist. Rather than continually slapping the rationalist card on the table and declaring science the trump suit, he brings an element of humility to his writing. So much so that he’s willing, almost eager, to engage religion. Not in debate, but in conversation.

What could be more humbling than living in an infinite but expanding universe? Since the days of Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton we’ve known that the apparent reality of both our own lives and that portrayed in Holy Writ is inaccurate. The earth doesn’t hold still, and the sun doesn’t rise or set. The universe isn’t a layer-cake with Heaven above and Hell beneath. Instead it’s mind-numbingly massive. The only appropriate response, it would seem, would be silent awe. Marcelo Gleiser, whose work I’ve mentioned before, is a rare scientist. Rather than continually slapping the rationalist card on the table and declaring science the trump suit, he brings an element of humility to his writing. So much so that he’s willing, almost eager, to engage religion. Not in debate, but in conversation.

The Prophet and the Astronomer is a wide-ranging book that is tied together around the theme of the end of the world. A few weeks back we had yet another brush with a biblical literalist declaring the end of all things. Gleiser, although his book was published over a decade ago, was called in to comment in various places. This book opens by discussing ancient ideas of the end of the world. These are necessarily religious ideas. We don’t fully understand ancient concepts, but enough remains for us to see that apocalypses have their origins in Zoroastrian thought. Judaism encountered such thinking and the book of Daniel ran with it. Early Christians also had the world’s end on their minds, and the book of Revelation developed into a full-blown apocalypse. The world, or at least the western hemisphere, has never been the same since. Centuries of living under the threat of a cataclysm that could come at any second surely takes its toll.

Gleiser then shifts to the real harbingers of potential apocalypses. Comets and asteroids still exist and could theoretically deliver what the Bible implies might happen—a fiery end to the planet. This is sobering stuff. But the book doesn’t stop there. Bidding adieu to the dinosaurs, The Prophet and the Astronomer sweeps us into this great, expanding universe and how it may end, scientifically. Black holes and the heat death of the universe can be truly terrify. What is remarkable about the book, however, is that Gleiser openly acknowledges that science can’t give the comfort and meaning that religion can. Instead of saying, “be tough, face facts” he suggests that scientists might consider a narrative that adds value to a cold, dark universe. That’s not to say some of the story isn’t technical and some of the concepts aren’t difficult to grasp, but it is to suggest that science and religion should sit down and talk sometime. Hopefully before the end of the world.