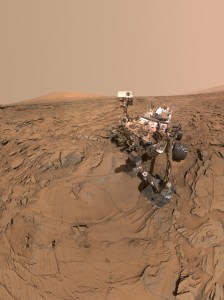

It brings tears to my eyes. A little guy millions of miles from home. The only spark of acknowledged intelligence on the entire planet. It’s his birthday and he’s singing “Happy Birthday” to himself. It’s downright depressing. The guy, however, is the Mars rover Curiosity. It is a machine. The headline, however, jerks an emotional response from all but the coldest of individuals: “Lonely Curiosity rover sings ‘Happy Birthday’ to itself on Mars.” It’s that word “lonely.” It gets me every time. Then I stop to think about machine consciousness again. Empirical orthodoxy tells us that consciousness—which is probably just an illusion anyway—is restricted to people. Animals, we’re told, are “machines” acting out their “programing” and not really feeling anything. So robots we build and send to empty planets have no emotions, don’t feel lonely, and are not programed for sadness. Even your dog can’t be sad.

Amazing how short-sighted such advanced minds can be.

We don’t understand consciousness. We’re pretty wowed by our own technology, however, so that building robots can be brought down to the level of middle-school children. We build them, but we don’t understand them. And we may be losing part of ourselves in the process. An undergraduate I know who works in a summer camp to earn some money tells me a couple of disturbing things. Her middle-school-aged charges are having trouble with fine motor skills. They have trouble building basic balsa-wood airplanes. Some of them can’t figure out how paperclips work. One said she couldn’t write unless she had access to a computer. This camp worker’s supervisor suggested that this is typical of the “touchscreen generation.” They’re raised without the small motor skills that we’ve come to take for granted. Paperclips, it seems to me, are pretty intuitive.

Some 34 million miles away, Curiosity sits on Mars. An exile from Earth or an explorer like Henry Hudson? Or just a machine?

Machines don’t always do what you tell them to. I attended enough high school robotics sessions to know that. Yet at the local 4-H fair the robots have a tent next to the goats, the dogs, and the chickens. We’ve come to love our devices. We give them names. They seem to have personalities. Some would claim that this blog is the mere result of programing (“consciousness”) just as surely as Curiosity’s programmed singing to itself out in the void. I’m not for turning back the clock, but it does seem to me that having more time to think about what we do might benefit us all. This constant rush to move ahead is exhausting and confusing. And now I’m sitting her wondering how to get this belated birthday card delivered all the way to Mars.