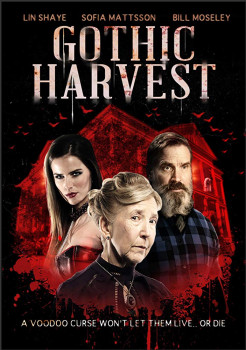

The title sounds promising. Gothic Harvest. But the movie in no way lives up to it, even with its vampires vs. voodoo theme. So, during Mardi Gras a group of four coeds decides to party in New Orleans. Of course, this is the capital of American voodoo. While drinking themselves to oblivion, one of them gets picked up by a local and taken back to the family home. There, of course, she’s kept as food for the “vampire.” An aristocratic woman who fathered a child with a slave has received a curse—she and her child remain alive, she aging, while the rest of the family is arrested at their present age. (Really, the story makes little sense, so don’t ask.) They need young blood to keep the aristocrat alive so that they can continue living. In the right hands such a story might’ve made a passable horror film. These weren’t the right hands.

It’s a good thing I’m trying to develop an aesthetic for bad movies. The acting is bad, the dialogue is bad, the writing is bad. Is there a moral here? Don’t go partying during Mardi Gras since you might get picked up by a family under an ancient curse? And would it really hurt to do a second take of scenes where an actor stumbles over their lines? I don’t know about you, but to me the title Gothic Harvest suggests that lissome melancholy of October. You can start to smell it in the air in August and you know something is coming. Honestly, I’m not sure why more horror films don’t capture that successfully. I’m always on the lookout for movies that will catch my breath in my throat with the beauty and sadness of the season. They are few and far between.

So, like a clueless coed during Mardi Gras, I’m lured into movies whose titles promise such things. One of the movies that I, inexplicably, saw when I was young was the James Bond flick, Live and Let Die. Roger Moore had taken the reins from Sean Connery but that film set my expectations for both the Big Easy and voodoo. I’ve only been to New Orleans once, and that during a conference. It was before the revival of my interest in horror. Successful horror has been set there, of course. The one thing Gothic Harvest gets right is the evocative nature of Spanish moss. And the opportunity to try to learn to appreciate bad movies.