It takes a lifetime to make a reputation. In high school my teachers and classmates knew mine well: religious and full of integrity. Going on to do three degrees in religious studies confirmed all that (at least the former). Something that nobody seemed to pick up on was that I liked watching monster movies. I did less of it in college, but still watched some heavy-duty fare (including David Cronenberg) when I was in seminary. Once I married life looked more optimistic and I really didn’t feel the need to watch what is called “horror” any more. Sure, we occasionally saw films everyone was talking about, but in general I moved away from the genre. It took Nashotah House and its aftermath to bring me back. In any case, my reputation seems to be such that now when people who know me see religion and horror together they think of me. I’m touched.

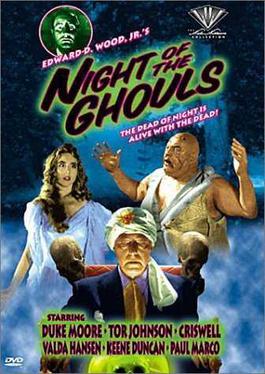

A regular reader of my blog sent me an article from The Guardian titled, “Schlock horror! Meet the family who made lurid movies for the Lord.” It should be pretty clear, if my integrity is intact, that what I’m trying to do is figure out how these things fit together, religion and horror. That they do is obvious, but how? In any case, this article plugs a book by journalist Jimmy McDonough, The Exotic Ones. The book explores the Ormond family and their odd filmmaking. The father, mother, and son triad, made a living producing cheap, questionable films. After a plane crash, which they survived, they became religious only to find their minister wanted them to keep making their bad movies for evangelistic purposes. The films they produced for the church had religious themes, but used well recognized horror tropes, anticipating, if you will, Left Behind and its ilk. Like a Thief in the Night scarred many of my generation.

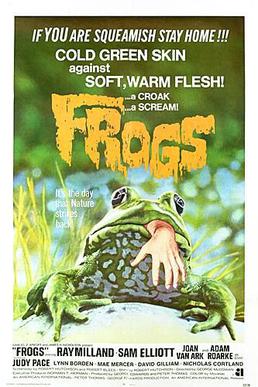

I’m probably not alone in not recognizing any of the movies the article discusses. If I’m reading correctly, Tim Ormond, the son and sole surviving family member, stopped making these films after the death of his parents. In any case, I have been developing a fascination with bad movies. The fact that they’re even made and released is incredible to me (mostly the released part). Many of us end up reacting to life rather than following the plans we had for it. Fate—call it what you will—has a way to stepping in. For one family, however, fate led them to a church that paid them for what they wanted to do. Many of the rest of us find just the opposite and we end up watching horror to try to understand.