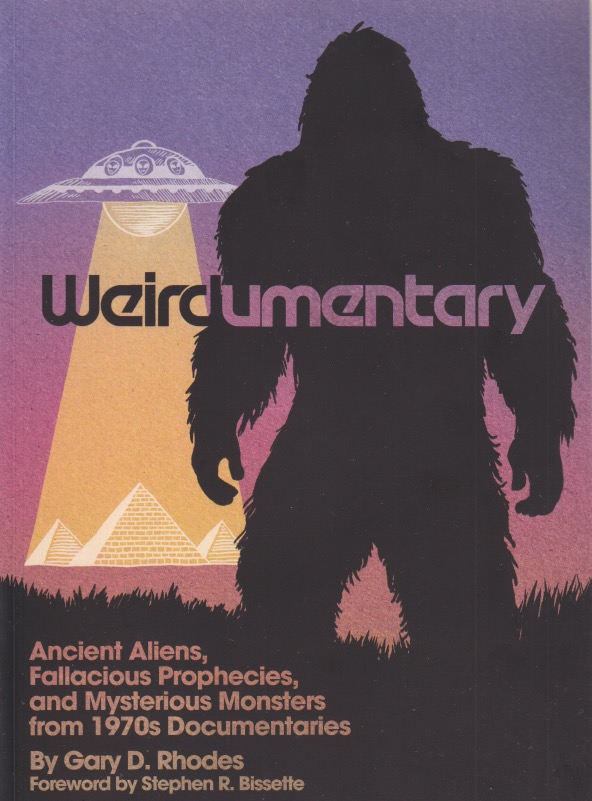

I’ve read Gary D. Rhodes before and found him informative and enjoyable. Although I hope his recent offering Weirdumentary moves beyond its ideal readership, I suspect I’m among that class. I was alive and somewhat aware of cinema during the period under discussion—the 1970s—and I even saw a few of these films in the theater, as well as watching some of the television offerings. I think Rhodes is correct in pointing out that this genre was a product of its era. And what a strange time the seventies were! I grew up watching the series In Search of…, which is discussed at some length here. But before I get more into it, I should explain that a “weirdumentary” is a pseudo-documentary that has characteristic features such as dramatic recreations, questionable authenticity of at least part of what it covers, and often a famous personality as a host.

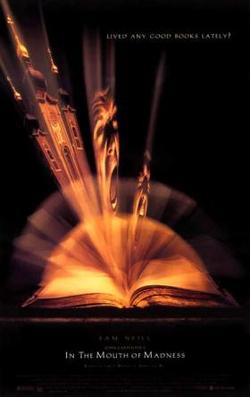

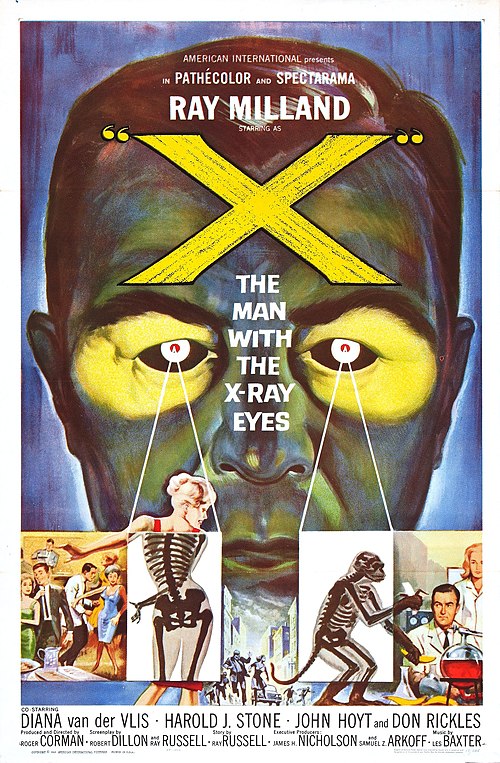

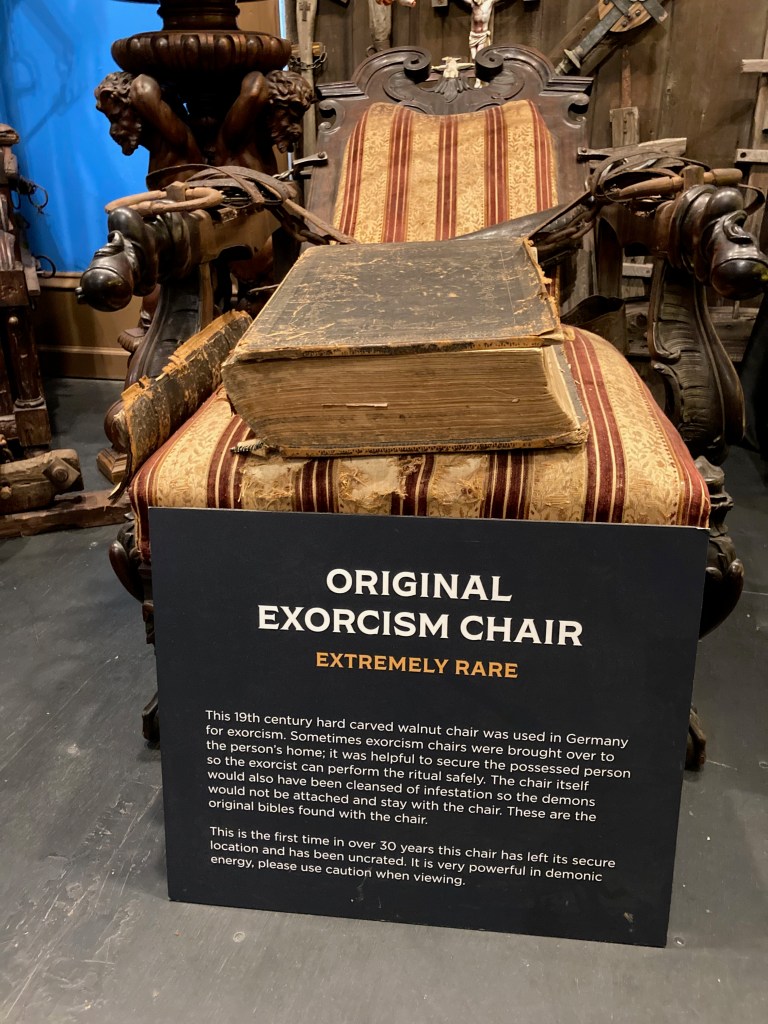

The book is handsomely illustrated with pictures that will offer a nostalgic rerun of the seventies for some of us. It divides the material into eight sections: the proto-weird, ancient aliens, UFOs, the Bermuda Triangle, the paranormal, mysterious monsters, speculative histories, and prophecies. The proto-weird are this kind of documentary from before 1970, and the rest of the categories sometimes bleed into one another. Not to detract from this excellent book (it’s often quite witty), my mysterious mind thinks a straightforward chronological treatment might’ve worked better. “Paranormal,” for example, could cover quite a few of these topics. Still, the organization of a book can be a personal thing and this layout, with “prophecies” at the end, works well. A number of speculative religious films make the list, including In Search of Noah’s Ark and Late Great Planet Earth, both of which made it to my small-town theater, and drew me in back in the day.

I also admit to having spent some of my summer earnings to see Mysterious Monsters. And maybe Chariots of the Gods—although I can’t remember for sure. I certainly read the book. Rhodes begins by explaining how 2001: A Space Odyssey set up viewer expectations for such films as these. I definitely saw that one when I was young. So the ideal readership here would seem to be those born in the sixties who were old enough to see these movies (and television programs) when they were making their initial rounds in the next decade. Kids suggestible enough to believe the pseudo-science of many of these offerings, who would grow up to look back on them nostalgically. Written with a light touch, but true appreciation of the subject, this book was a great way to relive one of the strange segments of my early life.