“Anything free is worth saving up for.” That’s a line from one of my favorite movies of all time. Free, though, can mean many things. The “free cookie” is something good to entice you to buy more. It often works. Free, for a person, indicates the ability to do what we want (within the constraints of capitalism, of course). But “free” can often mean cheap, overly abundant. I like to decorate our lawn with rocks, which are often free, but if you want decorative rocks you’ve got to pay for even the ground beneath your feet. So it is that when I attend book sales I marvel about the fact that Bibles are nearly always free. It occurred to me again when I attended a spring book sale a few months back. I always look through what’s on offer—call it an occupational hazard.

I used to attend the Friends of the Hunterdon County Library book sale in New Jersey. I believe it is the largest I ever visited. I used to get there early opening day to stand in line. One year, one of the volunteer friends came out and announced that they had a really old Bible (only 1800s) that would be $100. People do, however, tend to donate Bibles to book sales in great numbers. I suspect organizers are reluctant to put Bibles in the trash. They also know that people aren’t going to shell out money for them, so they try to give them away. What does this say about being free? Is it desirable to be so abundant that you’re left on that table in the back while everyone else is leaning over the more exciting items on offer? There’s perhaps a message here.

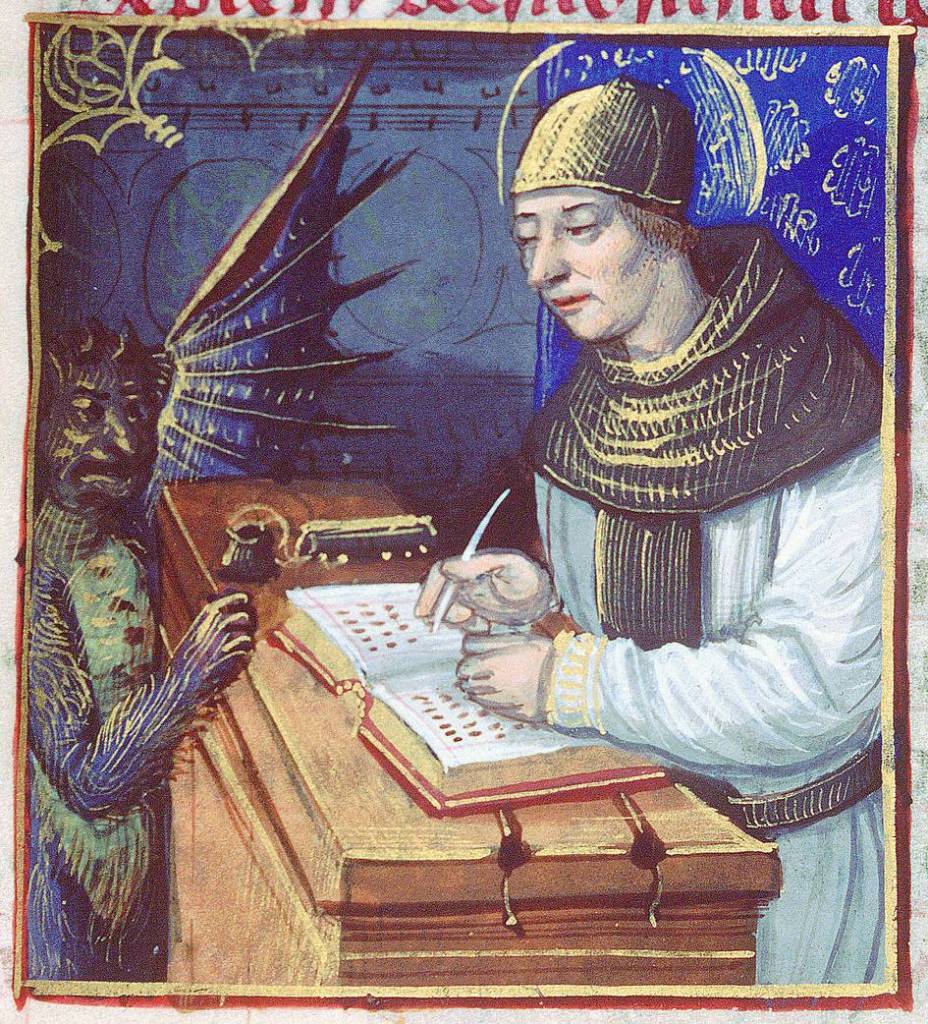

Of course, Trump is selling Bibles for $60. That’s a bit steep, even for an academic Bible (which his is not). It might be suggested that this $60 is cheaper than free. Now, I work with Bibles that are sold at a profit. One thing I’ve learned is that Bibles sold are always for profit. Those who are honest admit what they do with the lucre. Although he’s tried to keep it under cover, the Trump Bible does funnel profits to the GOP hopeful. Yes, he is making money off the Bible and wants to be elected. If that happens, freedom will disappear. He’s said as much at his rallies. Looks like stormy weather to me. There are organizations that give away Bibles. Somebody, however, pays for them. In this strange experiment of a country, anything free is worth pondering. Nothing, it seems, comes with no strings attached.