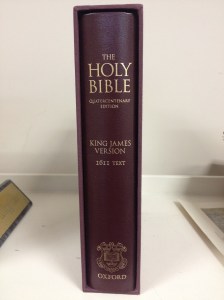

The Bible’s been back in the news. Specifically the Bible and politics. Like twins separated at birth. Jeff Mateer, Trump’s nominee for a federal judgeship, has gone on record saying Satan’s plan is working. Perhaps even more stridently, Roy Moore down in the Sweet Home state has been quite vocal that the Christian God is the one who makes America’s laws. Standing on “biblical principles” that have nothing to do with the actual Bible, politicians have found a biblically illiterate population a field of white-headed grain ready for the reaping. As sure as the sparks fly upward. The response in the educated class is predictable. Cut any funding for departments studying religion. Haven’t you heard? It’s dead!

Having grown up in a conservative, religious family, and working my way through a doctorate in a closely related field, I’ve been watching in dismay as the past quarter-century has been marked by decreasing positions in religious studies. If you can pull your eyes from the headlines surely you’ll agree that religion is something we just can’t afford to study. Wasting resources, it is, since if you teach economics you have an actual shot at the White House. Yee-haw! Pull out your six-shooter and celebrate! And no, “yee-haw” is not etymologically related to the name of the deity of ancient Israel. It’s only a matter of time before discovery of who’s been uncovering whom’s nakedness becomes public. Then you just need to say the Bible says nothing about divorce. It’s okay, nobody will bother to look it up. Intellectuals will scratch their heads—why didn’t somebody tell us religion actually motivated people?

Universities (consider the name!) used to be places where the value of all subjects was acknowledged. Of course, where there’s knowledge there’s money to be made. Once you’ve gone to the dark side, there’s no coming back. Departments that don’t earn mammon must go the way of the mammoth. Times have become so hard it’a almost like schools want to open Religion Departments just so they have something to shut down. We’ve got to keep those fields that are actually important going. Never mind if your funding depends on a government increasingly elected on the basis of perceived religious faith. Since the Prosperity Gospel is now in vogue, economic departments are always a safe investment. Slap a copy of the Ten Commandments on the courthouse lawn and follow the crowds to DC. Good thing none of this matters, otherwise me might be in real trouble.