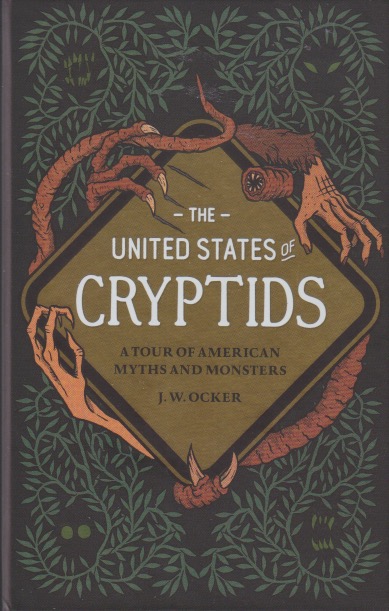

J. W. Ocker and I have a few things in common. We’re both Edgar Allan Poe fans. We both have an interest in the odd. And we like to visit places where something strange is commemorated. It gives me hope that there are likely more such people out there. I read Ocker’s Poe-Land a few months back and knew I’d be coming back for more. The United States of Cryptids caught my eye. This book is for fun, but with a serious subtext—our world is a weird place. Dividing the country into four regions: Northeast, South, Midwest, and West, Ocker traveled across the country looking for stories, or better yet, memorial statues and/or plaques, of cryptids. Defined broadly. These cryptids can be sightings of something unusual, folklore, or, in some cases, confessed hoaxes. He makes the point repeatedly that cryptids make for great tourism opportunities. There are people like me that will seek out such places, given half the opportunity.

Quirk Books, which has been unfortunately experiencing some difficulties of late, functions as a sort of home to oddities. And cryptids fall into that category. Ocker does point out, on a serious note, that any animal reported to have been encountered prior to scientific description was a cryptid. Perhaps the most famous case is the gorilla, which many non-Africans believed to be mythic until one was actually found. Or the coelacanth. In any case, discussing cryptozoology is a dicey thing to do. If you take it too seriously you’ll be ousted from polite society and if you handle it with too much humor, true believers will shun you. Ocker manages to find the middle ground here with a book that is fun to read and yet gives you ideas of places to visit or concepts to explore.

Reading Ocker’s books makes me think that maybe I take things a bit too seriously from time to time. That’s one reason that it’s important for me to read authors like him. I’m plagued with a need to know. Not everybody is, of course. I do tend to take things with an amount of earnestness that others sometimes find too intense. It’s probably my childhood that’s to blame. That doesn’t mean I can’t enjoy a lighthearted treatment of unknown animals. And I do try to keep a somewhat open, if critical mind. There’s a line, sometimes fine, between having fun with and making fun of. Ocker enjoys the odd enough to know which side of that line to walk. Or drive. Now, where did I leave my car keys?