A few weeks back, for my weekend fix, I watched Scream. I hadn’t seen the movie when it came out in 1996, but having seen so many references to Ghost Face I felt I was missing out on something. I was disappointed, however, at the relative lack of religious imagery or dialogue in the film. Such motifs are so common in horror films that I’ve come to depend on them. In fact, there was nothing supernatural in the movie at all. This weekend I decided to follow it up with the sequel that many claim is better than the original, Scream 2. It is the same self-aware exposé of horror gimmicks and tropes, providing several clever frights along the way. But this time there was more religion. Not that it was overt or central, but it was clearly there. My thesis was bolstered a little bit since the storyline felt the need to come back and pick up what was mostly lacking from the first film.

A few weeks back, for my weekend fix, I watched Scream. I hadn’t seen the movie when it came out in 1996, but having seen so many references to Ghost Face I felt I was missing out on something. I was disappointed, however, at the relative lack of religious imagery or dialogue in the film. Such motifs are so common in horror films that I’ve come to depend on them. In fact, there was nothing supernatural in the movie at all. This weekend I decided to follow it up with the sequel that many claim is better than the original, Scream 2. It is the same self-aware exposé of horror gimmicks and tropes, providing several clever frights along the way. But this time there was more religion. Not that it was overt or central, but it was clearly there. My thesis was bolstered a little bit since the storyline felt the need to come back and pick up what was mostly lacking from the first film.

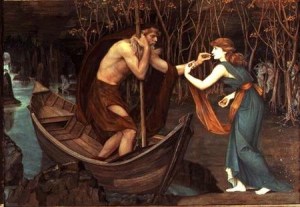

Sidney draws first blood in the sequel by comparing a sorority to a religion. Not much, but a start. We find out that Sid has taken up drama in college, where she has been cast in the role of Cassandra, the prophet of Troy cursed with never being believed, although always being right. In the truly disturbing scene from the play we’re shown, Zeus himself comes down and points a godly finger at the frightened girl. The real religious imagery, however, comes toward the end of the movie when Derek is tied up, cruciform style, by his frat brothers for giving away his letters. He plays the role of the sacrificial lamb as Sid comes face-to-face with the Ghost Face duo, and when his dead body is lifted up on the stage prop, the camera angle reveals either an angel or an ascending deity, arms spread out as if on a cross. Life has been laid down for life, a distinctly religious theme.

What would horror be without resurrection? The villain always comes back from the dead, having easy access to that which is denied the regular mortal. This factor alone suggests that most horror films are transmuted religious fulfillment wishes. We live in a time when religion seems to have lost its transcendent power, and yet we long for resurrection. Horror movies tell us it is available, but at a very steep price. Perhaps it is an unintentional motif, but it is a pattern that occurs so often that it feels integral to the very conception of the scary movie. That which we long for the most is the most terrifying. Horror films aren’t for everyone, but their popularity shows, on some level, that our society hasn’t given up on religion just yet. Scream 2, the resurrection of a wry, witty, and somewhat gory original, brings fear and religion together once more. Religion, like the horror villain, never really goes away.