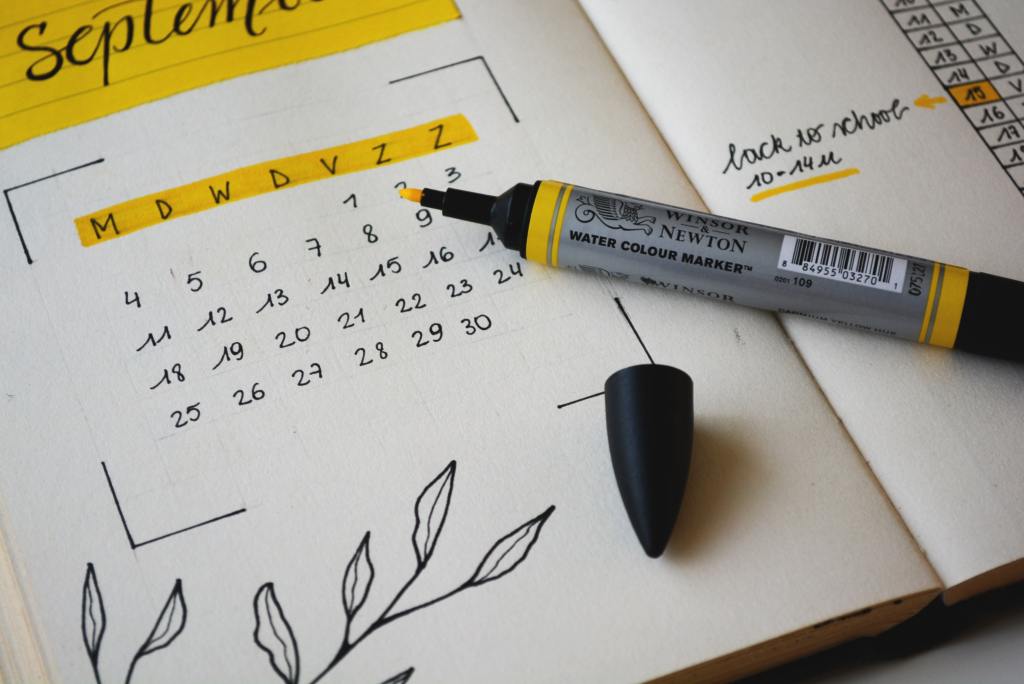

I appreciate help. I really do. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed in this world and others offering to help out are welcome. But you do have to wonder about algorithms. They seem to lack human sympathy. And perhaps the ability to count. Every year I enter the Goodreads Reading Challenge. I would read without it, of course, but having that extra pressure doesn’t hurt. Because of my convoluted mental makeup, I try to get things I have to do done early. That means I want to finish my reading challenge before I have to. In my commuting days I read about 100 books per year. When I stopped commuting I had to bring that number down by about half—frankly, I don’t know where the time went, but I do spend more awake time with my family, which is good.

So I’ve settled on setting my Goodreads goals at about 50-60 books per year. I often exceed it, depending on how many big books, or ponderous academic tomes I read. Lately I’ve set the goal at 55, which is just over a book a week. That seems doable to me. This year I achieved that goal in September, but that doesn’t stop me from reading, nosiree! I’m currently somewhere near the 60 book mark and I’ll keep going. Now the help I was referring to is this: Goodreads typically sends an encouraging email in October suggesting how to meet your goal. My message showed, via tracker, that I’d already met my goal, but telling me I could still meet it with these suggested books.

The books suggested are fine, I’m sure. And that this message was sent via some formula that I have no hope of being able to comprehend, I’m also sure. An algorithm, however, doesn’t feel for you. I’m relieved to have the goal behind me and to continue pressing on regardless. I could use some help in getting the lawn mowed, should an algorithm like to apply. I particularly resent having to do so while wearing a jacket and stocking cap. It’s time for the grass to be settling down for its year-end nap, isn’t it? Or maybe an algorithm could do my job for me. I guess that’s not funny, because that fate has befallen many humans, I suppose. Maybe the solution is simply to read more. That’s not a bad thing, but I don’t need an algorithm to get me to do it.