I don’t recall how I first learned about Mitch Horowitz’s work. I read Occult America as soon as I found out about it—it helped as I was transitioning to writing about religious culture (largely through horror films) since there’s a healthy dose of occult in horror. While still in publishing Mitch agreed to look at Holy Horror before it landed with McFarland. The thing about my life is that it’s too busy (9-2-5 isn’t a size that fits all) to keep up with writers I find fascinating. I hadn’t been aware of Horowitz’s continued, and continuing, book writing. As soon as I saw Uncertain Places: Essays on Occult and Outsider Experiences I ordered a copy. It brought back to mind the semester break at Nashotah House when I realized that to get anywhere near the truth you need to question and question boldly. I told my students that if they didn’t challenge their perceptions with reading during semester breaks they were wasting them.

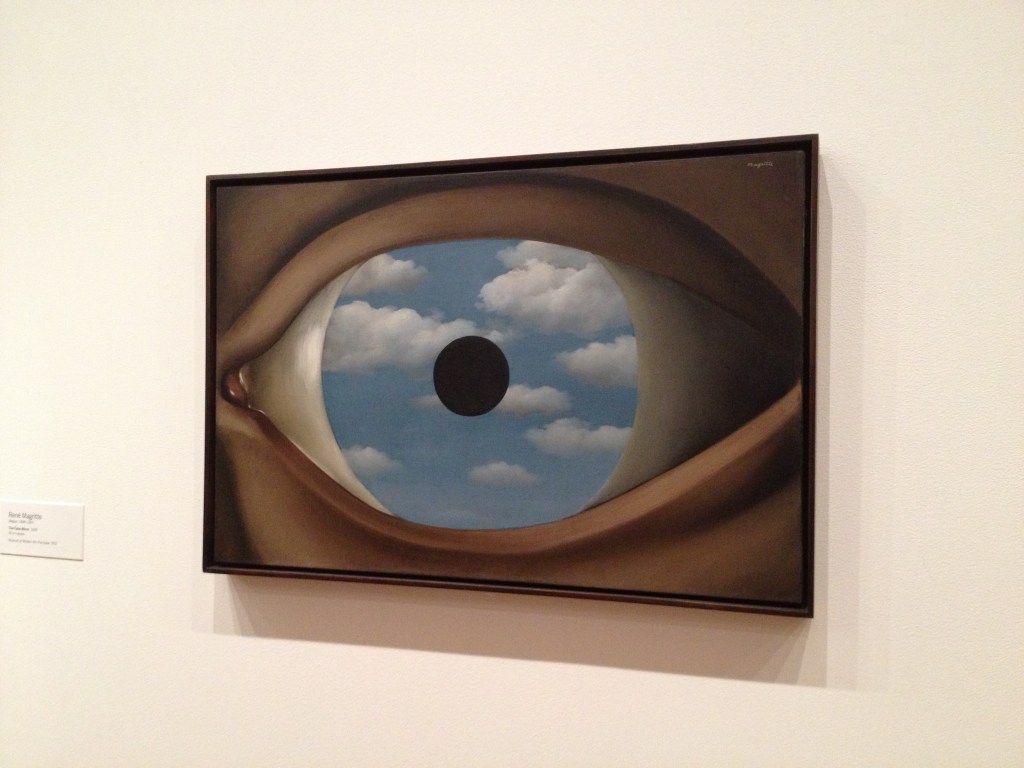

I met Mitch (although we’ve never seen each other in person) through our mutual friend Jeff Kripal. They both have the courage to question apparent reality and to not stop at the line that the wall of materialism throws up around the pursuit of knowledge. Uncertain Places is well titled. Like almost all collections of essays some speak to the reader more than others, but I found myself pausing frequently to consider what I’d just read here. One thought that keeps recurring is how even someone with a terminal degree can constantly feel like there’s so much more to explore. Horowitz is a seeker unashamed. And that also took me back to my past.

Growing up poor, I didn’t have many resources other than my mind to help draw some preliminary conclusions about reality. Like many red-neck families of the time we had a CB radio and we were each instructed to come up with a “handle.” I believe it was my mother who suggested “Searcher” to me. She knew that I would never stop looking. Uncertain Places is the work of another searcher—one who’s less fearful than I tend to be. (I’m working on it.) Reality, it seems clear to me, is far more subtle than most of higher education has taught me that it should be. We try to make occult scary and demonic but Horowitz is, like yours truly, an historian. Those of us who explore the history of religion can find ourselves in some pretty unusual, one might say uncertain, places. And rather than dismiss what we see there, we take a closer look.