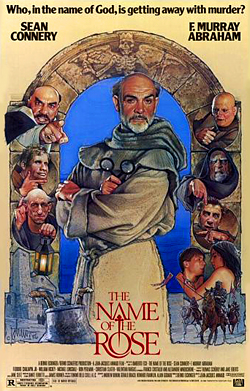

It was Edinburgh, my wife and I concluded. That’s where we’d seen The Name of the Rose. Edinburgh was over three decades ago now, and since the movie is sometimes called dark academia we decided to give it another go. A rather prominent scene that we both remembered, however, had been cut. If you read the novel (I had for Medieval Church History in seminary), you knew that scene was not only crucial to the plot, but the very reason for the title. In case you’re unfamiliar, the story is of a detective-like monk, William of Baskerville, solving a suicide and murders at an abbey even as the inquisition arrives and takes over. It isn’t the greatest movie, but it does have a kind of dark academic feel to it. But that missing scene.

Of course, it’s the sex scene between Adso, the novice, and the unnamed “rose.” Sex scenes are fairly common in R-rated films, often gratuitous. But since this one is what makes sense of the plot, why was it cut in its entirety? Now the internet only gives half truths, so any research is only ever partial. According to IMDb (owned by Amazon; and we’d watched it on Amazon Prime) the scene was cut to comply with local laws. More to the point, can we trust movies that we stream haven’t been altered? I watch quite a few on Tubi or Pluto and I sometimes have the sneaking suspicion that I’m missing something. How would I know, unless I’d seen it before, or if I had a disc against which to compare it? There was no indication on Amazon that the movie wasn’t the full version before we rented it.

The movie business is complex. Digital formats, with their rights management, mean it’s quite simple to change the version of record. Presumably, those who’ve pointed out the editing (quite clumsy, I’d say) in reviews had likely seen the movie before. Curious, I glanced at the DVDs and Blu-ray discs on offer. The playing time indicated they were the edited version. Still, none of the advertising copy on the “hard copy” discs indicates that it is not the original. Perhaps I’m paranoid, but Amazon does run IMDb, and the original version is now listed as “alternate.” Now that I’ve refreshed my memory from over three decades ago, it’s unlikely that I’ll be watching the film again. I’ll leave it to William of Baskerville to figure out why a crucial scene was silently cut and is now being touted as the way the story was originally released.