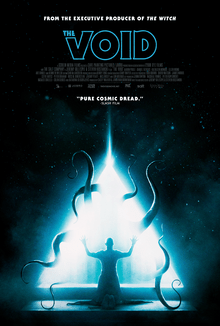

Lovecraftian horror translates to film unevenly. Even when it’s successful, as in Color Out of Space, it really isn’t that close to reading Lovecraft. “The Colour Out of Space” is among my favorite Lovecraft stories. To me, it feels perhaps his closest to Poe, and Poe is my personal muse. I knew that it couldn’t be made cinematic without changing things a bit, and that it would be pretty gnarly. I was correct on both counts. In very broad brush strokes, the movie follows the story: a colorful meteorite on an isolated farm begins changing the crops and the people who live there. Instead of crumbling, however, they are struck by the color and become other. The mother and her youngest son, for example, are fused together creating one of the most cringe-worthy scenes I’ve watched in a long while. The movie emphasizes family, even when things go horribly awry.

Defying Lovecraft’s well-known avoidance of focus on female characters, the movie’s focal point in Lavinia accords with Poe’s concern for threats against beautiful women. She’s the teenage daughter of the family and the film opens with a scene where she uses Wicca to try to heal her mother of cancer. The love between Nathan (Nicolas Cage) and his wife is movingly shown. The movie was recommended to me during a conversation about Nicolas Cage in horror. Maybe it’s because he’s in so many movies in total, I’d never really considered him a scream king, but he’s nailed the role quite capably, with the notable exception of The Wicker Man. Color Out of Space is pretty extreme body horror but the movie is artistically done. You almost don’t mind feeling violated in that way because of the visual appeal of the non-horror focused parts.

The acting is uniformly strong. In a nod to Lovecraftian fans, Lavinia uses the Necronomicon as the basis for her Wiccan rites. Some of the scenes seem to reference Evolution and others eXistenZ. Transforming the action from Lovecraft’s setting in the early twentieth century to the early twenty-first is done pretty well. The family is isolated when the meteorite prevents electronics, including cars, from working. The movie does offer some alien creatures, unlike Lovecraft’s basic story. And these creatures point to a planet with tentacly beings that naturally tie this story into the Cthulhu mythos. Lovecraft’s own story doesn’t make this move, but of course, the Cthulhu mythos only really developed among his fans. In all, Color Out of Space exceeded my expectations, even though it was a box office flop.