It’s an old story. In fact, it’s in the Bible. The enemies of Yahweh perish. Since Israel’s god could not be represented iconically, the story goes, an iconic ark stood in for the divine presence. After a certain unpleasantness with the Philistines, the ark was captured and taken to the temple of Dagon. There, the statue of Dagon fell down in worship before the ark. Philistine priests, embarrassed for their deity, set the statue upright again only to come back the next morning to find their god not only toppled, but decapitated. I’ve always found this story intriguing. I wrote an academic article about it some years ago, which, as far as I can tell, has been ignored by subsequent scholars of Dagon. Of course, the Philistine god eventually went on to fame at the hands of H. P. Lovecraft. Today most scholars are far too parsimonious to care about that, so I’m left to follow my imagination when it comes to the old gods.

This past week, on my way to work, I spied a mannequin fallen in the Garment District. There used to be hundreds of fabric stores around here. I’m always interested in those that remain. Cloth is so basic to human needs. The mannequin was behind glass, behind a chain fence. She’d clearly fallen in the night. She was decapitated. Of course, Dagon came to mind. I’m sure that others walking by the store had the same thought. Fallen before the invisible almighty, an idol meets its end.

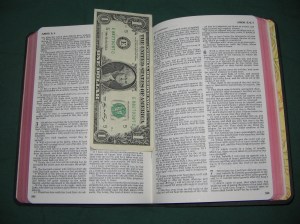

Once upon a time, I’m told, biblical literacy was common. I don’t mourn its passing because I believe society has become sinful, but I do mourn it because the stories are timeless and important. There is something very poignant about the idea of a foreign deity falling, headless, before an even more powerful, invisible foe. That foe these days is the equally omnipresent and omnipotent dollar. After all, I am standing in Midtown Manhattan where the only language that everyone can speak is that of Mammon. Writers of fiction and erudite scholars beyond the reach of mere mortals ponder the great mysteries of ancient gods. The rest of us walk the streets to our assigned places so that we may participate in its endless worship.