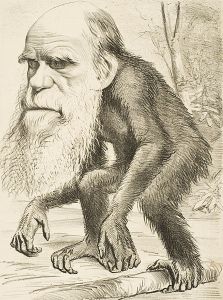

A recent Guardian introspective on Richard Dawkins reminded me of the dangers of idolatry. Dawkins, an internationally known intellectual pugilist, the article by Carole Cadwalladr intimates, is as human as the next guy when you can catch him off the stage. Ironically, it is evolved primate behavior to adore the alpha male, but, at the same time, to prevent abuse of power and to get away with what you can behind said alpha male’s back. We are worshipping creatures, at least when it suits our best interests. Anyone who’s been intellectually slapped down (something yours truly has experienced multiple times) knows that it is an unpleasant experience that one doesn’t willfully seek out. We try to keep out of the way of those who assert themselves, preferring the safer route of just doing what we’re told and apologizing for something we know isn’t really our fault. It’s only human.

The media have provided us with ever more expansive ways to build our “experts” into gods. Dawkins, a biologist, has become one of the go-to experts on religion. The media don’t seem to realize that hundreds of us have the same level of qualifications as Dr. Dawkins, but in the subject of religion. Many of us are not biased. And yet, when a “rational” response to religion is required, a biologist is our man of the hour. Granted, few academics enter the field in search of fame. Most of us are simply curious and have the necessary patience and drive to conduct careful research to try to get to the bottom of things. We may not like what we discover along the way, but that is the price one pays for becoming an expert. Those who are lucky end up in teaching positions where they can bend the minds of future generations. Those who are outspoken get to become academic idols.

I have no animosity toward Richard Dawkins or his work. I’ve read a few of his books and I find myself agreeing with much of what he says. Still, a trained academic should know better than to “follow the leader” all the time. (Some schools, note, are better at teaching independent thought than are others!) The academic life is one of doubt and constant testing. Once you’ve learned to think in this critical way, you can’t turn back the clock. One of the things that those of us who’ve studied religion know well is that all deities must be examined with suspicion. Especially those who are undoubtedly human and who only came to where they are by the accidents of evolution. I’m no biologist, but I inherently challenge any academic idol. I’m only human, after all.