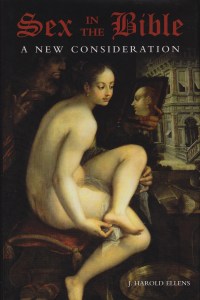

The word polymath used to be applied more easily. In these days of highly specialized training, it is difficult to have expert knowledge in more than a couple of areas. The two areas, sexuality and scripture, dealt with in J. Harold Ellens’s Sex in the Bible: A New Consideration, are such zones of specialization. Students of the Bible have recently begun an intensive exploration of how sex fit into the ancient worldview. Ellens’s book surveys all of the biblical legislation about sexual matters and a fair number of the stories involving the same, with the sensitivity of a professional counselor. Indeed, his practical knowledge of human sexual development and psychological needs based on it should inform society’s understanding of scripture. The Bible is no pristine book. Neither is it a romance novel. Still, ancient people were not as shy about sex as post-Victorians tend to be. The Bible is often frank on the subject.

The word polymath used to be applied more easily. In these days of highly specialized training, it is difficult to have expert knowledge in more than a couple of areas. The two areas, sexuality and scripture, dealt with in J. Harold Ellens’s Sex in the Bible: A New Consideration, are such zones of specialization. Students of the Bible have recently begun an intensive exploration of how sex fit into the ancient worldview. Ellens’s book surveys all of the biblical legislation about sexual matters and a fair number of the stories involving the same, with the sensitivity of a professional counselor. Indeed, his practical knowledge of human sexual development and psychological needs based on it should inform society’s understanding of scripture. The Bible is no pristine book. Neither is it a romance novel. Still, ancient people were not as shy about sex as post-Victorians tend to be. The Bible is often frank on the subject.

The main danger of a project like this is trying to decide where to take the Bible literally and where not. Ellens, while he has some training as a biblical scholar, falls into a familiar trap. He assumes, as parts of the Bible do, that Israel’s neighbors were sexually depraved. Not only did they condone things like bestiality, according to Ellens, but they incorporated sexual deviancy into their worship. Ancient records, readily available for decades, give the lie to that outlook. Ellens makes the case that biblical writers had no way of knowing, however, that homosexuality, for example, is a biological predisposition that can’t be changed at will. Other sexual practices that are now considered normal and healthy were perversions in the biblical period. Medical science should inform our understanding of Holy Writ.

This is an argument Ellens can’t win. Passionate though he may be about how all of this just makes sense from a scientifically informed point of view, the fact can’t be changed that the Bible does condemn some sex acts outright. Even more damaging, in my opinion, is that the Bible clearly views women as the sexual property of men, and men regulate the sexuality of their females. Anyone arguing that the Bible is a moral guidebook in regard to sexual mores must face this issue head on. There’s no tip-toeing around it, even with verified psychological pedigree. The Bible is the product of a patriarchal structure that did not tolerate sexual practice outside prescribed limits. We now understand the same behaviors from a scientific point of view, but the written text doesn’t change. It is just that dilemma that makes it very difficult to be an expert on two fields so diverse as sexuality and biblical studies.