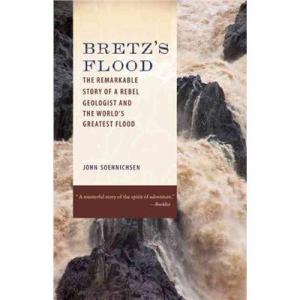

Sadly it is a rare occasion to read a truly stupendous book. There are lots of wonderful books in the libraries of the world, great and small. When I read a tome that brings two of my favorite subjects together in a genteel cotillion, subjects which are generally portrayed as aiming heavy weapons at each other from deeply sunk trenches, it deserves the epithet of stupendous. David R. Montgomery’s The Rocks Don’t Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah’s Flood is one of those books. By page 8 I was thinking that Montgomery was someone with whom I’d feel comfortable raising a glass and sharing a story. He is a rare, serious scientist who considers that maybe religious stories have something to tell us about being human. The book, as the subtitle indicates, is about the Noah myth. Geology is the science that has taken the brunt of (the relatively new religion of) Creationism’s umbrage. Still, like a rational scientist, Montgomery doesn’t get mad or fly off into hyperbolic denunciations. He takes his rock hammer and taps until the flood myth crumbles.

Sadly it is a rare occasion to read a truly stupendous book. There are lots of wonderful books in the libraries of the world, great and small. When I read a tome that brings two of my favorite subjects together in a genteel cotillion, subjects which are generally portrayed as aiming heavy weapons at each other from deeply sunk trenches, it deserves the epithet of stupendous. David R. Montgomery’s The Rocks Don’t Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah’s Flood is one of those books. By page 8 I was thinking that Montgomery was someone with whom I’d feel comfortable raising a glass and sharing a story. He is a rare, serious scientist who considers that maybe religious stories have something to tell us about being human. The book, as the subtitle indicates, is about the Noah myth. Geology is the science that has taken the brunt of (the relatively new religion of) Creationism’s umbrage. Still, like a rational scientist, Montgomery doesn’t get mad or fly off into hyperbolic denunciations. He takes his rock hammer and taps until the flood myth crumbles.

Unlike many sober writers on the subject, Montgomery considers the possibility that folklore may in fact give clues to science. Those cultures that have flood stories, he patiently explains, probably has reasons to tell such myths. In this one book we are taken on guided tours of the Grand Canyon, bits of the Himalayas, “ancient” Mesopotamia, the scablands of eastern Washington, and even the Creation Museum in Petersburg, Kentucky. At each station, we learn a bit about floods and rocks and fantasies. Although not a biblical scholar, Montgomery obviously did his homework and gives a fresh view of how Christians went from non-literalists in the first centuries of the church, through the scientific revolution, only to become literalists in the geologically very recent twentieth century. Creationism has nothing to do with real floods and quite a lot to do with personal insecurities.

It must be easy for scientists to trumpet bravado throughout the infinite universe. The scientific method is our best testable explanation for the physical world. Montgomery resists that temptation, realizing that religion does count for something after all. Religion evolved for a reason. Maybe it isn’t scientific, but it helps people to make sense of their world. Instead of characterizing religion and science as combatants in a war, Montgomery likens the opposition to a dance where the partners sometimes step on each other’s toes. I read his book dreaming my geological dreams, lost in deep time, and thinking that the world is maybe even more wondrous than miracles could ever convey. And we have occasional floods, and floods sometimes give us reasons for going on. There’s perhaps something religious about that.