I’m constantly reminded of the dangers of it. Interdisciplinarity, I mean. We all know the cliched image of the myopic professor unable to function in the world because he (and it’s normally a he) has spent all his time on one subject. Such people do exist, and they are generally institutionalized. (What else can society do with them?) More recently, however, the emphasis in higher education has been on interdisciplinary pursuits. Many modern doctorates span two areas and many modern professors show themselves as adept at activities beyond their “day jobs.” It is difficult, however, to be an expert in more than one thing. In my own case, I had interdisciplinarity thrust upon me. I’m therefore constantly being reminded of how tricky it can be.

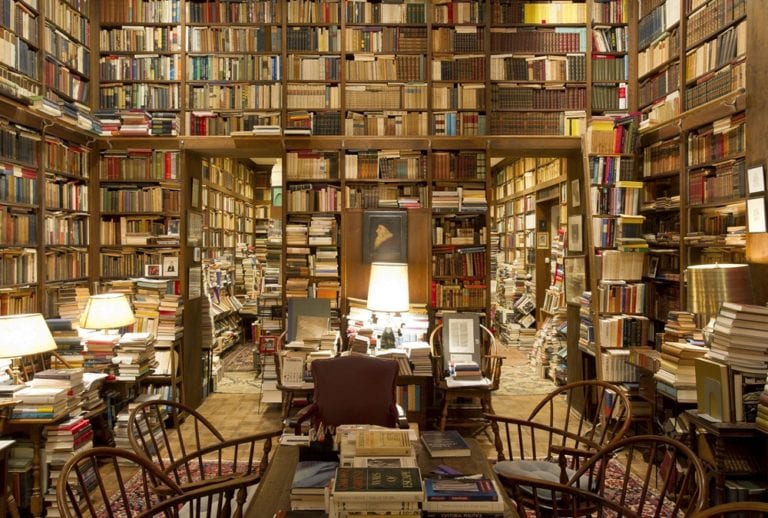

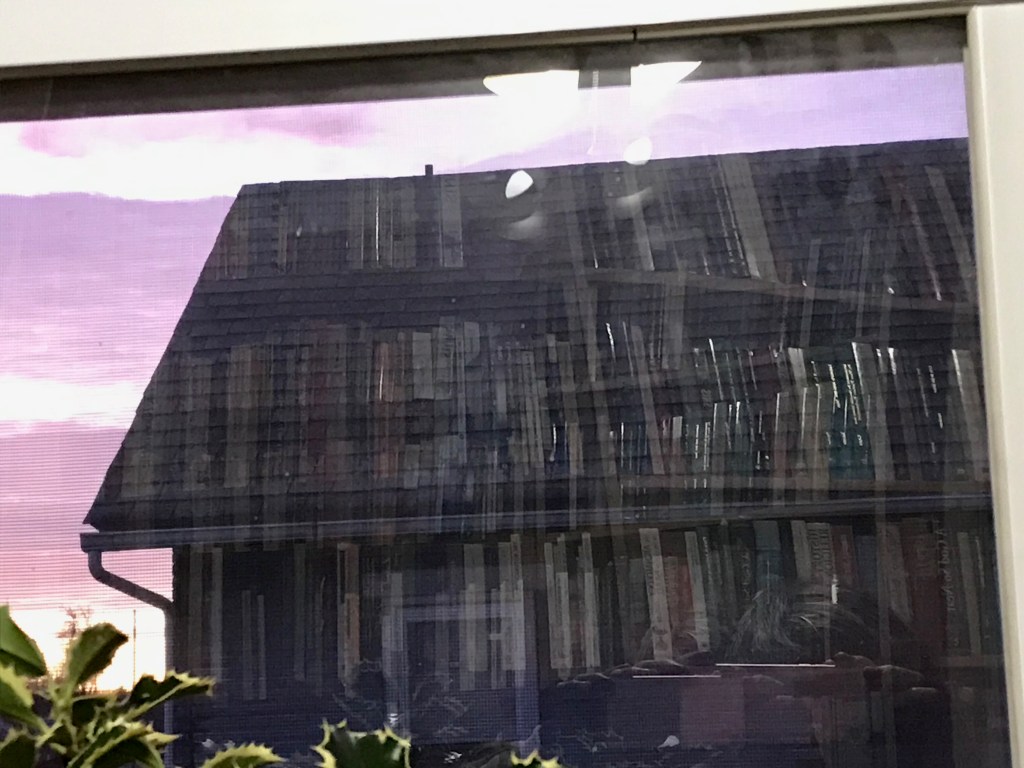

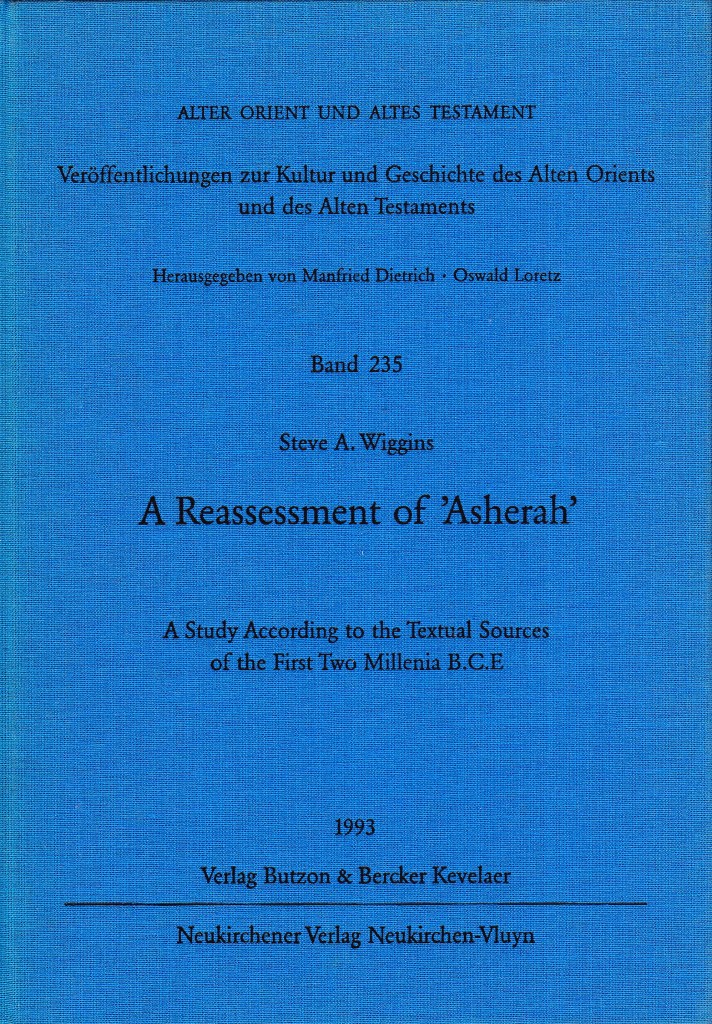

While hot on the trail of a new angle recently, I found what I thought was the only book on a subject. (All these years and am I still so naive?) I started reading only to discover that the topic had been explored many times before by scholars, beginning in the decade I was born. Clearly, if I wish to speak intelligently on this topic I should go back and start at the beginning. So it is with interdisciplinary work. Ironically, the book I was reading was itself interdisciplinary, demonstrating that old Ecclesiastes was right all along.

My own research journey has been one of restlessness. Others have seen this more clearly than I have. Once at the Nashotah House bookstore I had a discussion the the manager about rocks. This particular woman was certainly smart enough to have been on the faculty, and she saw things those of us that were didn’t. I concluded by saying I didn’t know why I’d been so taken by geology to which she replied, “If it wasn’t geology it would be something else. You’re curious.” She knew me better than I did. My curiosity about geology was deep and intense. (It still is.) I realized suddenly, it seems, that I knew too little about the very ground upon which I walked all day. What could be more basic than rock?

If anyone bothers to look at my full list of publications it quickly becomes clear that geology is absent. I never became an expert, but I still read about it and pick up interesting rocks. A small piece of rose quartz with a fresh fracture face stopped me in my tracks one very cold morning recently. I’m sure plenty has been written on the subject. The safest thing, however, is to become an expert on one thing. Safest, but dullest.