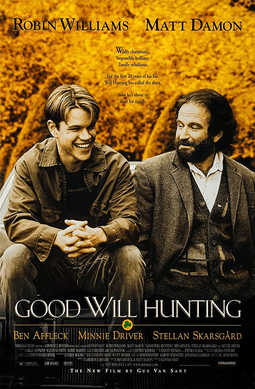

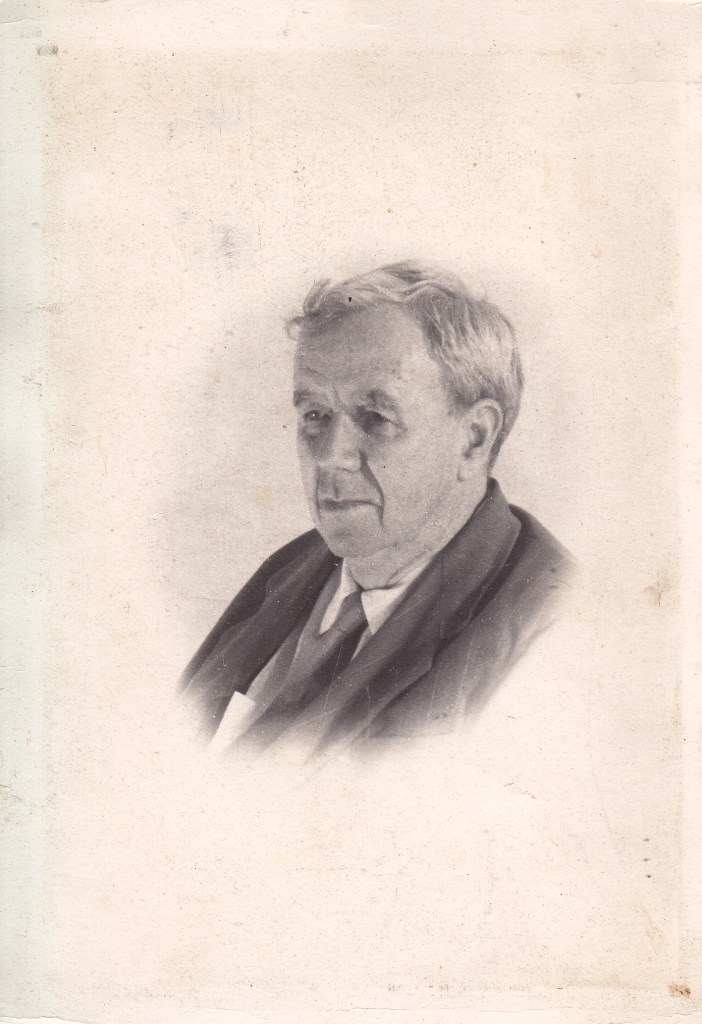

Back when it came out in 1997, I’d heard that it wasn’t a particularly happy movie. It was a good movie but it dealt with two damaged men. I was frightened off from seeing Good Will Hunting until it became associated with dark academia. Will Hunting is a genius but he was born in a bad part of town and earned himself a police record. He works as a janitor at MIT, but he also solves proofs instantly that professors labor over for years. The only way he can keep out of jail, however, is with the help of a therapist. Sean Maguire, who teaches at Bunker Hill Community College, is a psychologist who shares the background of Will’s rough neighborhood, but who recently lost his wife to cancer. He’s been traumatized by his life and the two come to realize, once Will learns to trust, that they have helped heal each other.

The darkness in this academia is mostly social. Even today, those of us who grew up in rougher locations don’t easily fit in academia. We’re blithely ejected from it in favor of those with more proper backgrounds. And connections. There were a few personal triggers for me watching this movie, but I had been wanting to see it for some time. Robin Williams, who plays Maguire, had starred in what may be the epitome of dark academia movies, Dead Poets Society. In both he plays his part convincingly. The term “dark academia” wouldn’t be coined, however, until the year after he died. Education is supposed to lead us out of darkness, but given what humans are, it creates its own form of gloominess. That’s probably why some of us find the category of dark academia so intriguing. Compelling enough to get us to watch films that will perhaps come with their own brand of trauma.

Children born into similar, or nearly identical situations may react to it quite differently. Although both in academic settings, Will and Sean have different experiences of it. With his life experience as a war veteran, and an educated world traveler, Sean invested his life in love and helping others. Will struggles with his fear of rejection to finally try to love someone more than upholding his own walls of self-protection. There’s some real depth here. It’s no wonder that the screenplay won more than a couple awards. It would take another couple decades, however, until the category of dark academia would be named. And if it hadn’t, I wouldn’t have risked watching this amazing movie.