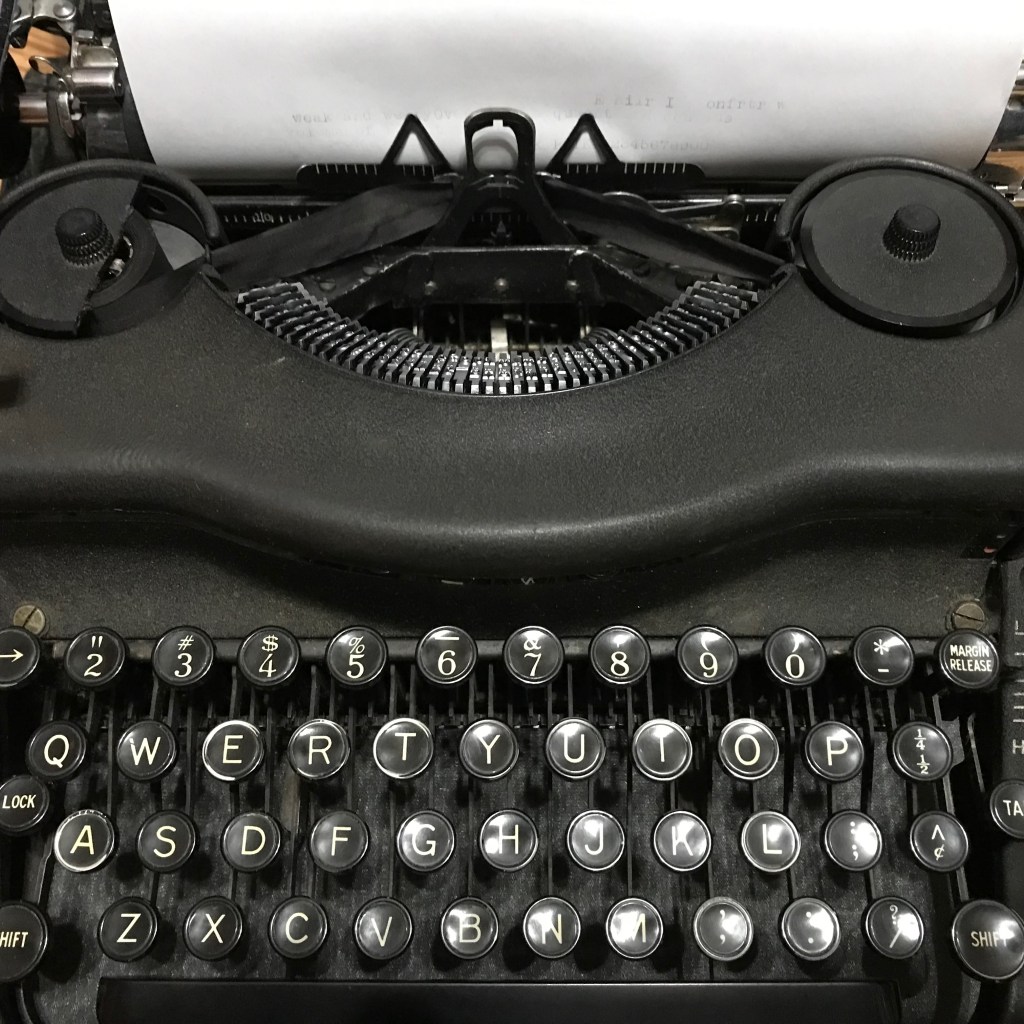

“Conference voice” is a phenomenon that began with my career malfunction. While teaching I attended the AAR/SBL annual meeting every year but one. Even the year that Nashotah House fired me I attended, through the generosity of a seminary colleague who’d left for a parish and who used discretionary funds to help me afford it. (Churches can actually help people from time to time.) In any case, I always met many colleagues at the meeting itself, and had many conversations. Besides, I taught a full docket of courses every year. Then the malfunction. I was eventually hired by Gorgias Press but I had to do adjunct teaching to make ends meet. I taught up to about ten courses per year at Rutgers, all in the evening. Then I was hired by Routledge. The commute to NYC precluded any adjunct work, so I settled into the quiet world of editing.

I also began attending AAR/SBL again. I came home with “conference voice.” After going for days, or even weeks, with no substantial conversation, I’d lost my lecturing vocal stamina. At the conference I had five days of back-to-back meetings, often in a crowded and noisy exhibit hall. I’m a soft-spoken individual (I can project when teaching) and my larynx was stressed by the concentrated five days of constant conversation. My voice had dropped in pitch by the time I got home and it took a few days to get better. I would lapse into cenobic silence for another year. After the conference I’d return every year with aching vocal cords. My family sympathized, but I really just don’t talk that much. Especially at work.

Recently I met a friend for lunch. I hadn’t seen him to chat for a few years so we spent over two-and-a-half hours talking. Part of it in a restaurant where I needed to raise my voice. I awoke the next morning with conference voice. This bothered me because I’d been invited to do a podcast episode about a horror movie and I faced an existential crisis: what does my real voice sound like? In my mind, my profession is teaching. The voice I had at Nashotah House, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh, Rutgers University and Montclair State, was my real sound, such as it was. Life has landed me in a situation where I seldom speak, and almost never to groups where I need to project. Conference voice is a reminder of what I was meant to do and what I, of necessity, must do.