I’ll always prefer indies but ever since James Daunt took over Barnes & Noble it’s become a much better place. I unfortunately didn’t get to any of Daunt’s stores while living in the UK, but unlike most corporate types, he gets books. He understands book buyers and, I like to think, he reads. I happened to need to stop into a local B & N recently on a Saturday morning. I got there a little early and I saw a line at the door. Naive as ever, I supposed it was a reading or writing group that’d be meeting there. The queue had one thing in common: they were all males between thirty and fifty years old. Who says men don’t read? I went in and got what I was after, and even browsed a bit. When I got to the register they were in line. Hands empty.

Then I noticed that as each one stepped to the register, the sales clerk would step back to a place behind the counter and come with the same thing for each one. As I got close enough, I saw that they were after Pokémon Prismatic Evolutions. The Prismatic Evolutions Poster Collection released just the day before when they were probably at work. The game sells for about a Franklin and the shelf was nearing empty by the time I finally reached the checkout. I looked back. At least five more guys had come in and immediately joined the line, no products in hand. I’ve never seen the appeal of Pokémon but I couldn’t feel smug because I was there because of an obsession as well. I didn’t buy a game, or cards (one guy bought 14 packs of the same card set, clearing that rack), but I was guilty nevertheless.

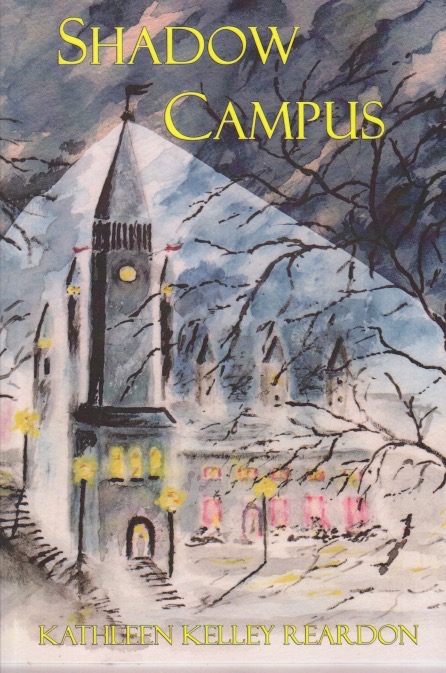

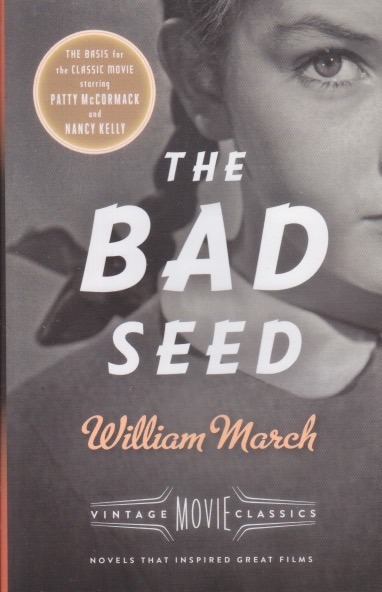

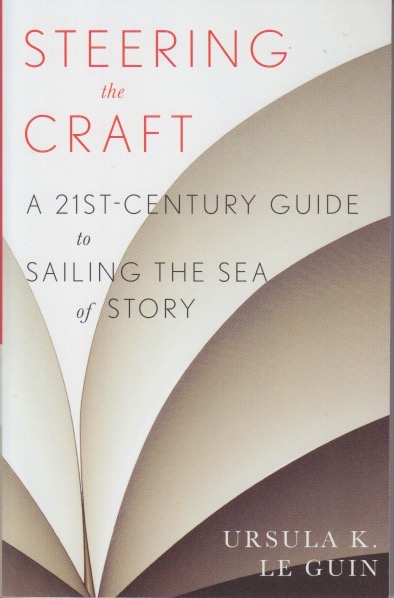

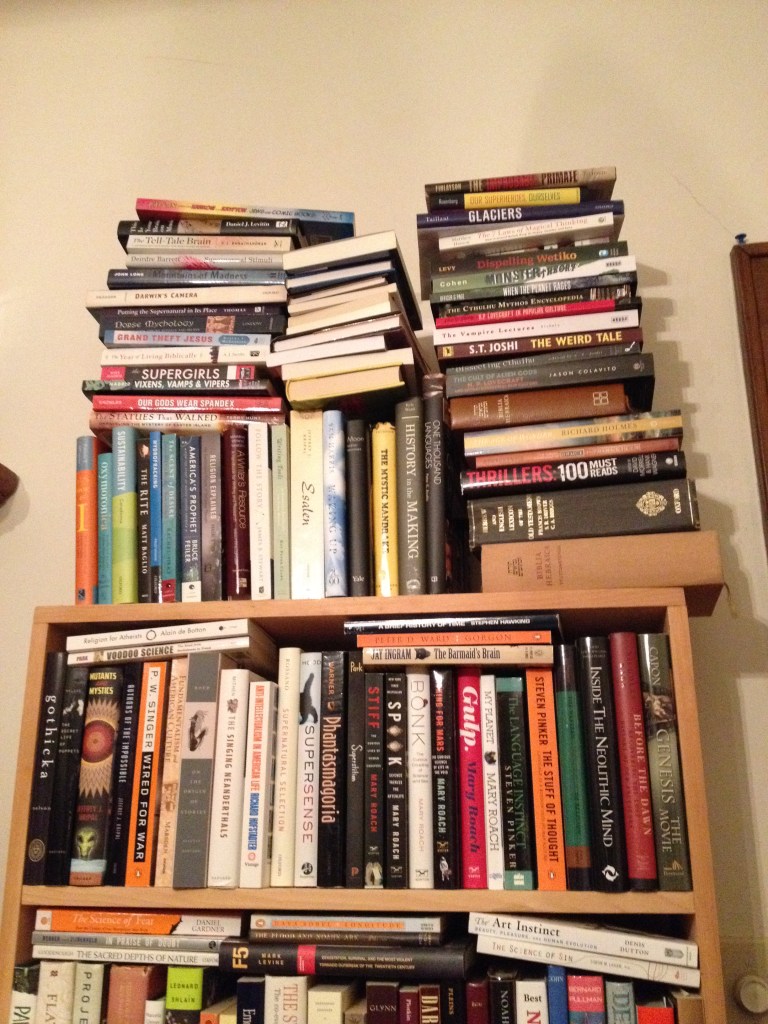

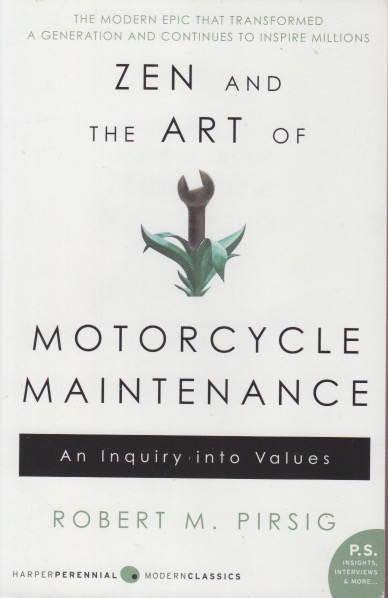

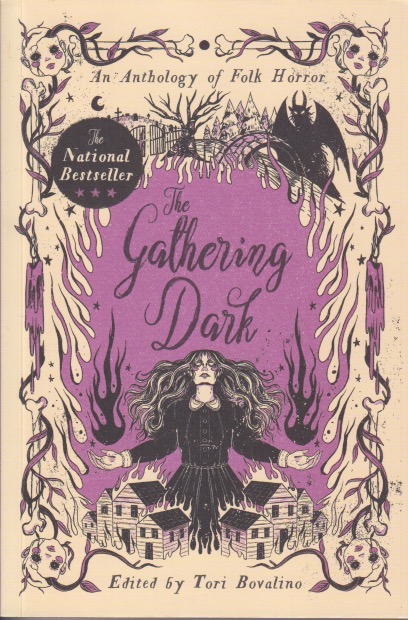

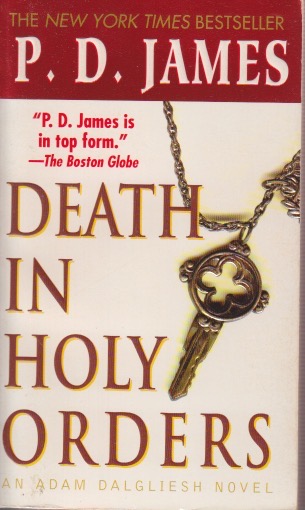

I’ve been fascinated by Dark Academia for some time now. That week, when I had also been at work, I realized that one of the books I had in that genre had been destroyed in what we refer to as “the flood.” (The story is here on this blog, but the short version is when we moved into our house, the movers stacked our boxes in the garage because they were complaining it was so late. Before I could move the boxes into the house—the day after the next, in fact—a torrential rain fell and many of the boxes got wet, destroying at least 100 books and some other items that can’t be replaced.) I was missing that particular book and it was old enough that I was pretty sure the local indies wouldn’t have it in stock. Daunt’s B & N did. So the line that morning contained a bunch of obsessive guys, but one of us, I have to confess, was over sixty.