You know how some email servers stock your inbox with ads? I almost never pay attention to them. Then one for Books by the Foot showed up. I had to click. The basic idea is simple enough: you want to look smart so you fill your shelves with books by a company that sells them by the linear foot. You can get color coordination, rainbows, old books, you name it. Now this isn’t a free ad. In fact, this is a rather sad state of affairs. I’m sure their antique books have been vetted for any real treasures, but the fact that people want to buy books just for display evokes, well, melancholy. I’m pleased that books retain their cachet as symbols of pride, but these are not books for reading. I’m left with mixed feelings. The website states that they have over 5 million books on hand.

At least they’re not selling ebooks. I love books. They are a wonderful symbol and I suspect they are among the most noble things that humans achieve. I grew enamored of books as I entered my tweens. I was terribly shy by that point. We had moved to a new, and rough small town where I really didn’t know anybody. Life, which hadn’t been exactly a picnic to that point, seemed to be getting scarier. So I read. And I never really stopped. Ironically, during my professorial days I had less time to read entire books. Those who’ve dabbled in higher education know that at even the hint of organizational skill you get bumped into administration, whether you want to or not. And administration is busy work. Yes, even professors have it too. In any case, when I got bumped back down to being a mere adjunct, I started reading a lot again.

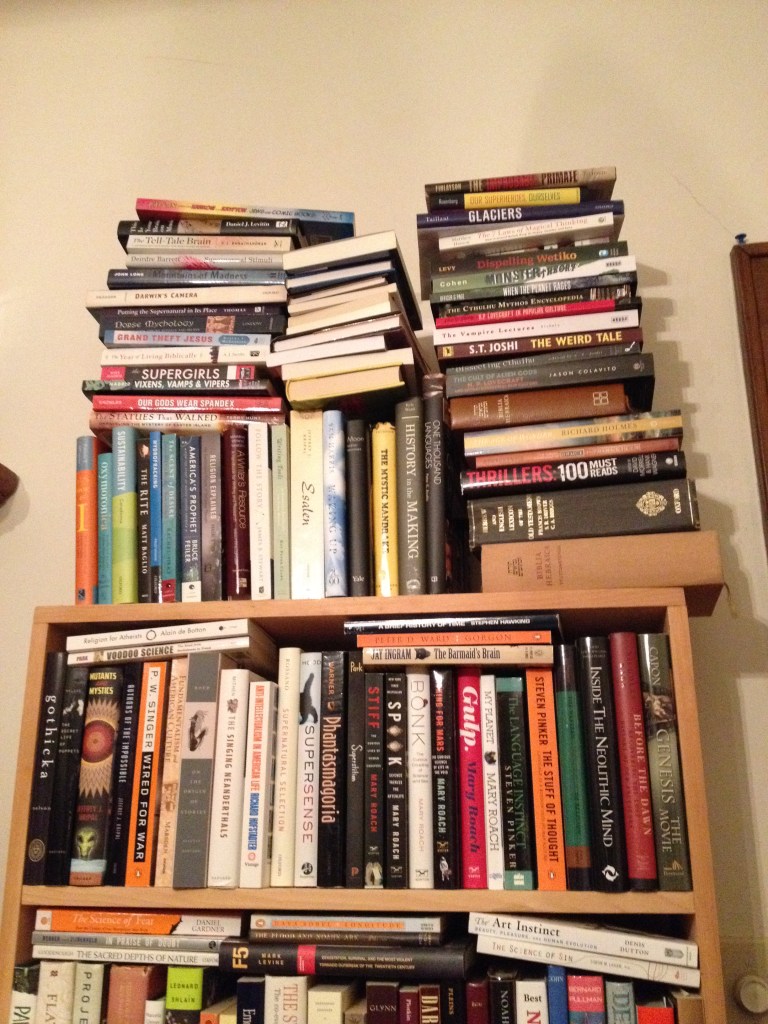

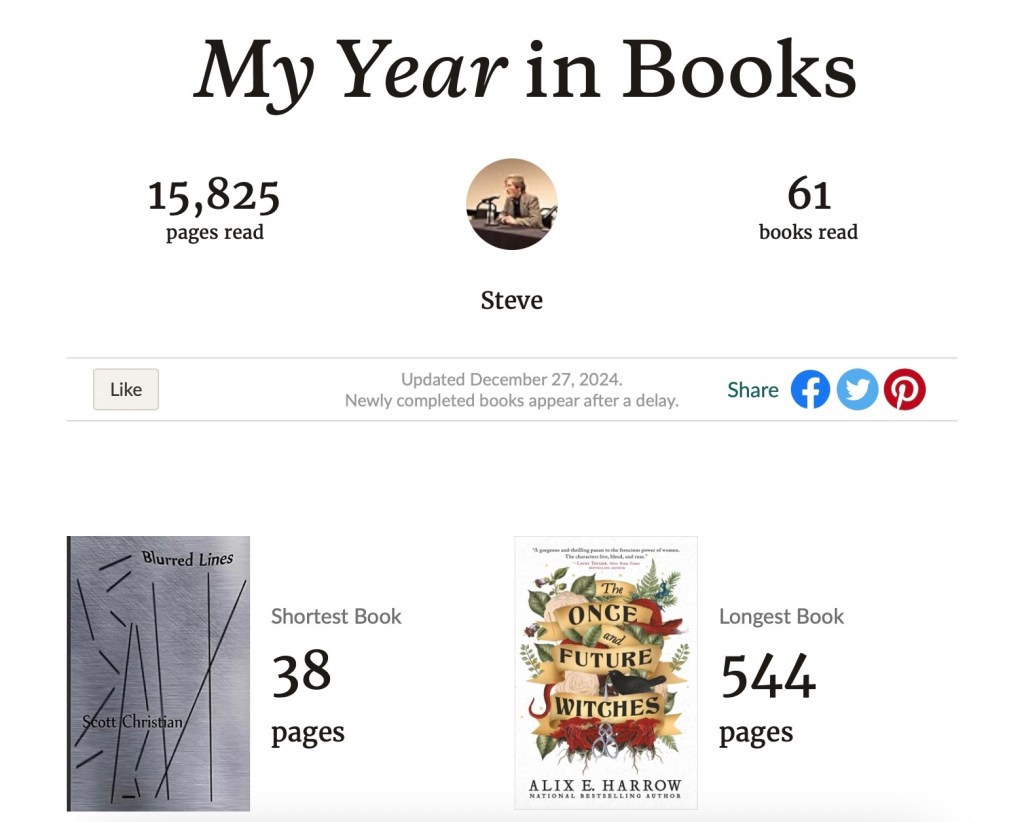

One time one of my bosses asked me how many books I had. This was early in the pandemic when we were seeing inside each other’s houses for the first time, via Zoom. My office is one of my main book repositories. (Along with the attic and the living room.) I answered truthfully that I’ve never counted. I started using Goodreads in 2013 to keep track of the books I read. In those early days I didn’t put everything in there (who hasn’t read a book they’re embarrassed to admit to once in a while?), but when I started the reading challenges in 2016 I did. Mine has been a life defined by books. Starting with the Good Book, and including many quite the opposite, I have earned books by the foot. But I’m not selling. Symbols have value beyond cash, at least in my mind.