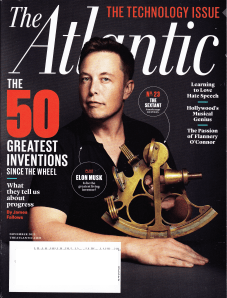

The crowd over at The Atlantic Monthly magazine are a formidable lot. Even with a Ph.D. and a modicum of writing ability, I’ve been frightened off from ever submitting to such an intellectual periodical. These are people whose opinions count. When The Atlantic named, in last month’s issue, the fifty most important inventions since the wheel how could I not peek? Especially when number 39 included a picture I recognized from my childhood in the cradle of the oil industry: Col. Edwin Drake standing outside a fledgling oil derrick in Titusville, Pennsylvania—just the next town up route 8. I felt like I might be somebody, by association. We all know that number one is best, so I wondered, as I flipped through the pages, what the most important invention was, although I suspected I already knew. The printing press, dating back to the 1430s, is certainly a contender, and was Atlantic‘s winner. Those of us historically inclined tend to think in regressions. The internet has forever changed our lives, but what is the internet without reading? (Okay, well, it is lots of funny pictures of cats and pornography, but you still have to be able to type in “cat” or “nude” or whatever, to bring you there.) It took the printing press to catapult reading from the academy to the hearth, and to reach that critical mass so that the Kindle could surpass the printed book.

The crowd over at The Atlantic Monthly magazine are a formidable lot. Even with a Ph.D. and a modicum of writing ability, I’ve been frightened off from ever submitting to such an intellectual periodical. These are people whose opinions count. When The Atlantic named, in last month’s issue, the fifty most important inventions since the wheel how could I not peek? Especially when number 39 included a picture I recognized from my childhood in the cradle of the oil industry: Col. Edwin Drake standing outside a fledgling oil derrick in Titusville, Pennsylvania—just the next town up route 8. I felt like I might be somebody, by association. We all know that number one is best, so I wondered, as I flipped through the pages, what the most important invention was, although I suspected I already knew. The printing press, dating back to the 1430s, is certainly a contender, and was Atlantic‘s winner. Those of us historically inclined tend to think in regressions. The internet has forever changed our lives, but what is the internet without reading? (Okay, well, it is lots of funny pictures of cats and pornography, but you still have to be able to type in “cat” or “nude” or whatever, to bring you there.) It took the printing press to catapult reading from the academy to the hearth, and to reach that critical mass so that the Kindle could surpass the printed book.

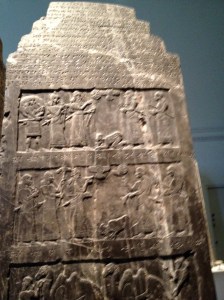

My interest in studying the Hebrew Bible for a doctorate actually included an ulterior motive. You see, the Bible was among the first books printed. As much as western civilization owes to the New Testament, my regressive thinking insisted that the New Testament was based on the Old. As I learned in seminary, the Old was based on an older, and that on an even older, in a pleasing kind of regression. I ended up in Ugaritic, the earliest known alphabetic language. The alphabet, I might contend, vies with the printing press for most important invention since the wheel. Before the alphabet writing was so cumbersome that only very skilled specialists could read written languages cobbled together from signs that represented letters and symbols and entire words and entire classes of words. But, ah, it was writing! Mesopotamians seem to have brought the idea into existence, specifically, those of ancient southern Mesopotamia that we call the Sumerians, who, incidentally, also invented the wheel.

Those of us in the book industry feel a constant worry in our stomachs when we look at book sales figures. Even in the most highly literate of social periods a very small percentage of people would actually purchase books (especially in the New World). With electronic media, that number has declined alarmingly. Still, the internet—number 9 on The Atlantic list—owes its life to good old paper (number 6) and pen (which failed to make the list at all). And paper wouldn’t have evolved without clay—the very substance of which early written myths claim that humans are made—and stylus. Thoughts locked in our clay heads cry out for expression. Some of us are compelled to put them in the form of written words for others to see. It’s just that we know our place and wouldn’t presume to send them to The Atlantic Monthly, or any other magazine, where they would be certain not to make the cut.