Returning home from my campus visits, I needed some brainless relaxation. Since we don’t have any television service at home, this means watching movies. I’d heard quite a bit about The Evil Dead over the years—a movie that was scary back in the 80’s when it appeared. Improvements in special effects and the intensity of engineered sound are capable of drawing a person into an alternate reality for a couple of hours these days, and the endless reiteration of earlier movie effects somehow robs the early thrillers of their impact. The Evil Dead, however, capitalizes on confusion about the menace and teeters on the brink of morality for the entire 85 minutes. Naturally, when looking for a source of fear, it seeks a religious agent. The source of the evil in the woods is narrated in a voice-over of the presumably dead scientist who has discovered Sumerian texts that release demons in the forest (mostly in the form of falling trees).

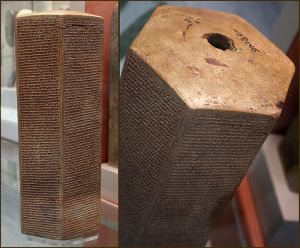

Sumerian is always a safe bet if you want a language that your viewers will not be able to identify. The earliest known recorded language, Sumerian is still difficult even for experts, and it conveys all the strangeness of long ago. We do know that the Sumerians recorded myths that involve what we might call “demons” today, but the possession of humans was a much later development—probably a pre-scientific way of explaining epilepsy. As our five students seek a weekend getaway in the woods, they become possessed and face the moral question of just when a person ceases to be human. At what stage does someone have the right to kill someone else? Perhaps unintentionally, the movie gives us the answer, “Never.” This kind of morality has a place in America, one of the very few “first world” nations in which the death penalty is still legal. Often promoted by those dead-set against abortion. Where do we draw the line saying a person has crossed over into the unforgivable other?

The Evil Dead has become a cult classic over the years. Its relatively low budget of less than half-a-million dollars brought an astonishing box office return on the investment. The gore, tame by more modern standards, does not mask that what is really at issue here: the question of right versus wrong. What is truly evil? Sumerians aside, what possesses people and drives them to destroy one another? The Evil Dead, like many horror films, reaches for a religious answer. As the supernatural fog begins to clear, however, we might not like what we see in the clear light of day. Religion may be an excuse, but the assaults upon one another are what Nietzsche famously called “human, all too human.” The sooner we clear our vision and pay attention to what is actually happening, the sooner we can combat the horror.